|

|

|

|

The main page related to the history of research is here. The present page has the following topics:

The famous Renaissance Art expert Panofsky (1892 - 1968) first became interested in the Voynich MS in 1931. This is recorded in correspondence of Anne Nill and ELV, preserved both in the Beinecke Library and in the Grolier Club (1).

Sometime in 1931 he came to New York as a visiting professor at New York University. In the course of his first half year term there, Miss Belle Greene of the Morgan Library showed him a photostat of one of the zodiac pages of the Roger Bacon cipher MS. The dating of this event is uncertain, but it must have taken place in 1931 (2). He at once recognised it as bearing a close resemblance to one page in a MS made in Spain for Alfonso the Wise, and asked to see the other pages. Miss Greene then contacted ELV, who came to meet him at the Morgan Library where she showed him the photostats. (According to Nill these were negatives and in poor condition, having greatly faded in some parts). After satisfying himself that no other page resembled either the Spanish MS or any other MS known to him, he became intensely interested and seemed to think that the MS was early, perhaps as early as the 13th century. He asked to see the original, and met with ELV and Anne Nill at the safe deposit vault on a Friday, where he spent two hours examining the MS. His first impression was still that it was early, but as he came to the female figures (in conjunction with the colours used in the manuscript) he came to the conclusion that it could not be earlier than the 15th century. A summary of his first impression after the two hours of investigation, was written down by ELV sometime letter, in a letter to James Westfall Thompson, written probably in 1932 (3):

- That it is neither Bacon, nor English work.

- That it was written in the south-western corner of Europe: Spain, Portugal, Catalonia, or Provence; but most probably in Spain.

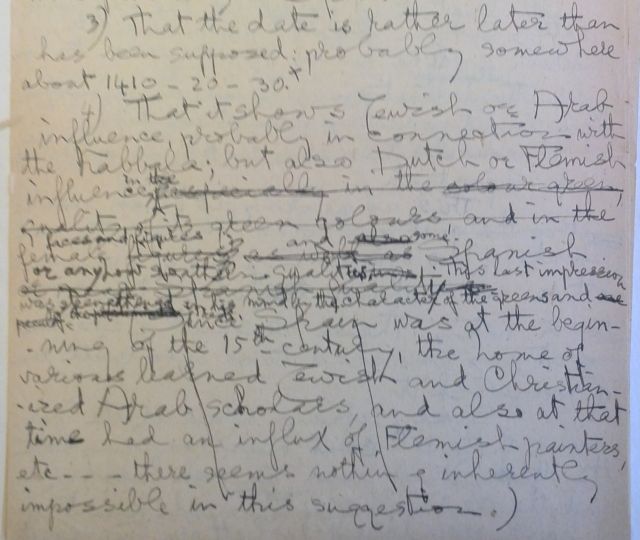

- That the date is later than has been supposed: probably somewhere about 1410-20-30. When looking at the Photostats he felt convinced that it was definitely earlier than the 15th century; but, on seeing the female figures more clearly in the original, changed his view.

- That it shows Jewish or Arab influence, probably in connection with the Kabbala; but also Dutch or Flemish influence in the female faces and figures and some Spanish or anyhow southern qualities. This last impression was strengthened in his mind by the character of the greens and red.

- That it is probably the surviving one of two volumes: the plant and star half of the work which doubtless included also beasts and stones.

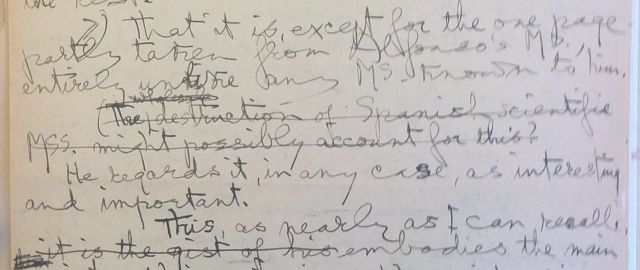

- That it is, except for one page partly taken from Alfonso s MS, entirely unlike any MS known to him.

He regarded it, in any case, as interesting and important. He went back to Hamburg, taking with him a complete set of photostats, and promising to ask some of his colleagues there to try if they can solve the problem.

It may be of interest to show the draft of this part of the letter in the hand of ELV, suggesting that she was struggling to correctly formulate his statements.

On 6 April 1932 ELV wrote a letter on the same subject to Belle Da Costa Greene. Following are some excerpts of it:

Dear Miss Greene,

I owe you a thousand apologies. It is upon my conscience that I never even wrote to tell you the final result of Professor Panofsly's examination of the cipher MS.

but no sooner had he sailed, taking with him a complete set of photostats and promising to enlist the help of his colleagues at the Warburg Institute - the very best thing that could possibly have happened - then first I and then Miss Nill went down with influenza. Since then we have been struggling to keep up with our work

[...]

Professor Panofsky will write to us when he has had the time to consult his colleagues. His present view is that the cipher MS is quite likely Spanish about 1420 (roughly), which would certainly account for the elaborate precautions against legibility.

The main importance of the above opinion of Panofsky lies in the fact that this is a very clear statement against the Roger Bacon theory of Voynich, only one or two years after Voynich's death.

Two decades later, Panofsky appears to have changed his mind on a number of aspects. On 16 March 1954 W. Friedman sent him a questionnaire with 15 questions. Panofsky sent a detailed response back to Friedman on 19 March, in his own words. Following is a summary of the questions and a full transcription of the answers (4).

In conclusion, Panofsky first thought the MS to be Spanish, with Jewish or Arab influences, and later changed his opinion that it could be German, probably influenced by his friend and mentor Richard Salomon (for whom see below). He believed the origin to be in the 15th Century, but allowed a later date in consideration of the tentative sunflower identification.

Parts of Voynich's own research can be reconstructed from his notes and letters preserved in the Beinecke library, and from his 1921 publication (7). Remarkably, for at least six or seven years after he acquired the MS, he did not pay much attention to the history of the MS, and he can only have paid a passing attention to the Marci letter. From a 1917 letter to cryptologist Edith Rickert, and some 1918 newspaper reports, it appears that by this time the Prague history of the Voynich MS was still completely unknown territory for him. Until 1918, Voynich believed that the Rudolf mentioned in the Marci letter was Rudolf I (1218-1291), contemporary of R.Bacon, and also that beside Kircher, only kings had owned the MS. He did not yet realise who exactly was Johannes Marcus Marci. But let us follow his steps.

Voynich took the MS to the US in November 1914, and as he reports in his 1921 publication (see note 7) at this time he had not yet seen the ex libris of Jacobus de Tepenec. From 1915 onwards he organised a series of exhibitions showing also his "Roger Bacon cipher MS", and his statements about this MS and the collection to which it belonged have been published in several newspapers. A short printed description of the manuscript, now preserved in the Beinecke Library (8), appears to have been used at these events, and includes:

This manuscript was bought by Emperor Rudolf for 600 ducats, an enormous sum at that time, and at the end of the XVI Century passed into the hands of King Ferdinand of Bohemia. Since then it has been locked up in one of the European royal collections, from which it was acquired by the exhibitor.

A Ferdinand is mentioned in the Marci letter, but this is King Ferdinand III of Bohemia. Voynich's reference to the end of the 16th Century can only refer to Ferdinand I, who preceded Rudolf II.

The Chicago exhibit in October-November 1915 must have attracted the interest of the historian of medicine Fielding H. Garrison, who wrote to Voynich on 2 November 1915, asking for permission to use the MS in his discussion of medicine around the time of Rudolf II. On 8 November, Voynich answered him saying that the Rudolf in question is Rudolf I (1218 - 1291) not Rudolf II.

Two years later, on 18 September 1917, Voynich answered a letter from Edith Rickert, a cryptography expert interested in the Voynich MS, and a collaborator of John Manly. In his answer he mentioned that the Rudolf in the Marci letter died in 1291 (i.e. he still believed that it is king Rudolf I).

By 1919, however, he had clearly realised that the Rudolf in the Marci letter was Rudolf II. He had asked a certain Miss Louise Loomis to translate the Marci letter for him, and he had started his search for the unknown seller of the MS to Rudolf. In a thank-you letter to her dated 10 April 1919 he announced his theory that it was John Dee who had sold the MS to emperor Rudolf II. This is also the time that Newbold started to work on his translation attempts, so this probably marks the time that the research of the Voynich MS really took off.

Early 1921 we see that Voynich is preparing for a presentation about the MS to be held on 20 April that year. In his preparations he concentrated on tracing the history of the MS by investigating the people associated with it. To research the Prague part of the history, he wrote to the Bohemian state archives on 9 February, inquiring primarily about Jacobus de Tepenec and Johannes Marcus Marci, suggesting that the two may have been associated with each other. He also inquired about 'Dr. Raphael', mentioning that he once taught Bohemian to the children of Ferdinand III (9). His letter (and the remainder of this correspondence) has been transcribed here.

In parallel he had his London employee Herbert Garland research Tepenec. The correspondence between Voynich and Garland has largely been preserved (10). The first answer from Garland is dated 14 February 1920, but from context it is clear that this should be 1921. Garland names some of the references he has used: Bolton, Jungmanna, Balbinus, and Backer (11). Garland writes again on 22 February, and Voynich sends him a thank-you letter on 25 February. The last two letters most probably crossed. Voynich states in these letters that his main source of knowledge about the court of Rudolf is Bolton (1904) (see note 11), which is a strongly romanticised account of Rudolf's court, and Garland points out its unreliability, and that it is largely based on the work of a certain Josef Svatek (12). The most important result for Voynich was that the mysterious Tepenec, who put his name on the MS, was none other than the 'Sinapius' whom Voynich knows from Bolton. He is exuberant that this proves that his MS was indeed at the court of Rudolf (13).

Voynich is still completely in the dark who is 'Dr. Raphael'. Garland seems to have spent most of his time in the library of the British Museum and was very effective, and Voynich continues to ask for information about people whose names he picks from Bolton: Mardochaeus de Delle (14) and Jacopo di Strada.

Fortunately for us, there are handwritten notes of Voynich in the Beinecke library, which contains lists of names of people related to Rudolf's court (15). It turns out that all of these names appear in Bolton, and they even appear almost exactly in the same order in which they appear in the book, and this is also true for numerous details that Voynich found interesting enough to note down.

His conclusion from this research, as we had already seen, was that a Roger Bacon MS was most likely brought to Prague by John Dee. Ironically, his list includes the name Sebald Schwertzer (16), who had in fact sold (or given) a Roger Bacon MS to Rudolf II (17).

Research from Garland futher went into the correspondence of Kircher, and he admits that he has not been able to find any letters to or from Marci, and suggests they have been lost. The correspondence of Kircher is listed extensively in De Backer (see note 11), and the entry is largely identical to that of Sommervogel (18), of which we know that it fails to mention the Carteggio Kircheriano that includes the letters from Marci. Garland also mentions that Miss Howe (who was working in the same London office of Voynich (19)) had written to Voynich about Marci's book 'Philosophia Vetus Restituta'. I have not seen this letter, but its importance is that this book mentions that Marci inherited the alchemical library of Georgius Barschius (20). Voynich must have remembered the statement in the Marci letter that Marci inherited the MS from its previous owner.

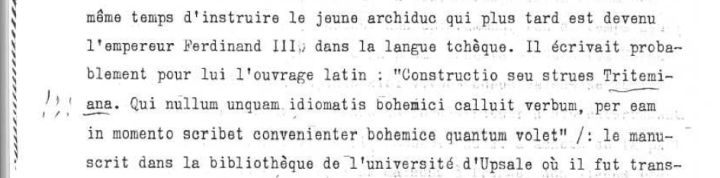

Fortunately for Voynich, he received a very long and detailed answer from Prague, from Dr. Ladislav Klicman, in March 1921, still in time for his presentation. This has been transcribed here (21). This included the many details about Tepenec and Marci (pointing out that they were not contempraries as Voynich had preseumed) that Voynich later used in his presentation and his paper (see note 7). It also finally resolved who was Dr. Raphael. Voynich was particularly interested to learn that Raphael Mnišowský was deeply interested in cryptography and had written a book in Trithemian style, and he put several exclamation marks in the margin of the letter at this point.

In his thank-you letter to Dr. Klicman, Voynich also inquired about Barschius, mentioning the inheritance, but there does not appear to be any answer.

From correspondence between Voynich and James Westfall Thompson, a historian of the University of Chicago, which took place after his 1921 presentation, we find that Voynich was still very seriously investigating the life of Dee, and Dee's ownership of Bacon manuscripts. Thompson managed to find out quite a lot about the origin of many Bacon manuscripts that Dee once owned, including hints of an encrypted MS, but this was only a few years before Voynich's death, and it is not clear what happened with this information.

The search for Kircher's correspondence also continued, for Voynich found out from a catalogue of Kircher's museum: De Sepi (1678) (22) that there used to be a 12-volume binding of Kircher's correspondence, and immediately realised (correctly as we now know) that this must be a valuable source for additional information about his MS (23). When Garland could not find any trace of this collection, Voynich decided to find out more about this from Henri Hyvernat, who was in Rome at the time. For an as yet unknown reason, Voynich did not write to Hyvernat directly, but asked his friend Wiliam W. Bishop to do that for him.

Hyvernat inquired in Rome about Kircher's correspondence, and his request reached the foremost expert, Fr. P. Tacchi Venturi S.J.. The latter's answer was that he himself had already searched for it in all the principal libraries in Rome, didn't know anything, and was not even aware of the fact that this was a 12-volume collection. He suggested that it was probably lost sometime between 1773 and 1824. In reality, the collection of some 2000 manuscripts, including Kircher's correspondence, had been moved from its hiding place in the Villa Torlonia in Castel Gandolfo (outside Rome) to the German college in the city, just a few years before, and Tacchi Venturi was personally involved in these affairs (24). His response demonstrates that the collection was still kept under lock and seal by this time, and he was not at liberty to talk about it.

The images of the handwritten letter by ELV have been shown here with the kind permission of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library of Yale University, New Haven (CT).

|

|

|

|