|

|

|

|

Information related to Voynich's acquisition of manuscripts from the Jesuits, which included the Voynich MS, has always been sparse. When, in 2014, I read in a publication by Arnold Hunt (1), that Voynich wrote to Belle Da Costa Greene of the Morgan library, that he had shown some of his 'fine Italian manuscripts' to the Reinassance art collector Bernard Berenson, I wondered if any records of that could have survived. Greene and Berenson are known to have shared a very extensive correspondence, of which at least the letters received by Berenson were still preserved in an archive in his original home, the Villa Tatti near Florence.

Since then, many new details about Voynich's acquisition have surfaced, and we largely know the history of this collection, how Voynich was able to acquire it, and why he had to keep complete confidentiality about this deal. Full details about these events may be read here. With this, the potential interest of any information related to the Voynich MS that could be found in this archive was certainly reduced.

However, we are fortunate that this correspondence was completely digitised in recent years, and is now available online >>via this link (2) . In the following, I will summarise a few of the pieces of information that struck me personally. I hope that more in-depth publications related to this subject may follow.

Much has already been written about Belle Da Costa Greene and Bernard Berenson. I do not need to add anything to that, nor would I be able to do them justice (3). I do think that it is of interest to just point out two personal aspects.

Voynich held Belle Da Costa Greene in the highest possible regard (as did many others). When E. Millicent Sowerby applied for a job in Voynich's London book business, she was told: "There is no place for women in rare book world ... only one woman had made success in rare-book field, and she is most remarkable woman in United States of America, Miss Belle Da Costa Green of Mr. Morgan's libraries in New York. No other woman could do what she has done; she is unique" (4).

With respect to Berenson, he lived in his Villa near Florence, and Voynich ran a book shop in the city. As a piece of trivia, both Voynich and Berenson were born in what is now Lithuania. We may only speculate that this could have created a mutual interest between the two men. Coincidentally, they were also born in the same year: 1865.

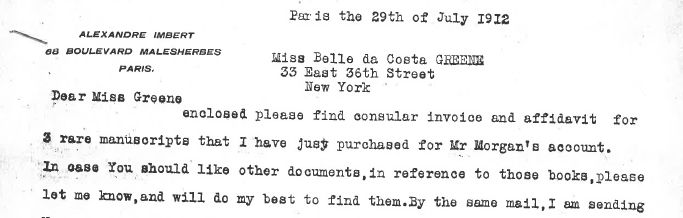

This letter from Voynich to Belle Greene is preserved in the Morgan Library archives (5), and Hunt quotes:

I usually try to procure the best available manuscripts in Europe, and this spring I showed to Mr. Berenson in Florence some very fine things. The best of these, however, have been sold to (1) booksellers in Florence (2) to Mr. Walters. I still have about 20 of these manuscripts ... but they are what I term trade manuscripts at prices varying from £400 to £800 and I doubt you would care to see them.

I only recently found out that the date of this letter is 6 July 1911, so a connection with the Jesuit manuscripts must be considered less likely. On the other hand, this might be clarified by the contents of the correspondence. Of the Jesuit collection, Voynich sold at least 7 to the Florence dealer Tammaro de Marinis, but I am not aware of any sale to Walters (6).

Thanks to the excellent search functions at the >>digitisation project web site, we immediately find that there are six letters that mention Wilfrid Voynich. Three of these have a direct bearing on the above-mentioned letter.

>>Letter 00153 of 17 May 1911

In this letter, Greene spells Voynich's name incorrectly, and she repeats some negative comments

about Voynich that she heard from Quaritch. If anything, this appears like a response to Berenson

mentioning Voynich's name in a preceding letter to her. The following letter confirms this:

>>Letter 00155 of 22 May 1911

and ff.

Only a few days later, and almost certainly in response to the same letter from Berenson, Greene writes:

I wrote Voynich & ordered a lot of incunabula etc. from his catalogue & then told him that you had written me of the fine mss. he had shown you in Florence and I told him I would be glad if he would let me know when he had mss. of this quality as I felt sure he would be glad to deal directly with us instead of via several other bookdealers.

This is clearly in response to the visit that Voynich relates in his later letter to Greene, and it is this that prompted Voynich to write that letter to Greene.

The theme of dealing directly, rather than via other dealers, was part of Quaritch's gripe with Voynich, and we will see more of this later.

>>Letter 00164 of 11 August 1911

In this letter, Greene writes that Voynich "wrote me a very florid letter probably on your account".

This, undoubtedly, is the letter quoted above. With this, we see that the Greene-Berensen correspondence gives an

accurate account of the known details, but unfortunately, we do not learn anything about the 'fine manuscripts'

that triggered this exchange.

Just to note, also for future reference, that exchange rates we will use here are 5 US$ to 1 £ and 5 French Francs to 1 US$ (7). The prices that Voynich mentioned in his letter would therefore be equivalent with $2,000 to $4,000 , so Voynich's comment about these as 'trade manuscripts' would certainly be an understatement. This price range coincides almost exactly with the asking price of the Jesuit manuscripts that De Marinis offered in his 1913 catalogue.

The next two letters deal with one of Voynich's more famous manuscripts from the Jesuit collection, namely the one with the miniatures supposedly from the hand of Giotto. As Hunt already notes, Voynich originally offered it for US$ 150,000 , but later sold it for half that price.

>>Letter 00230 of 17 March 1913

Greene writes:

By the way I received a letter from a man in London this morning saying that Voynich had shown him photographs of a wonderful manuscript he had containing 300 illum. by Giotto! - So "it" is very evidently the same mss. that Voynich showed you and Gruel offered to me - Voynich wrote me of some stuff he had and is sending me a few on inspection I'll write you about them as soon as I hear from him.

This tells us two things:

Let us search for any letters referring to Gruel.

>>Letter 00223 of 16 January 1913

Greene writes:

Gruel in Paris has written me of an early Italian manuscript which he has and which he says has paintings of Giotto or the School of Giotto! I am writing him today asking him to hold it until you come to Paris, without any obligation on my part to buy it - and will you be an angel and look at it for me and report to me? - I have not the slightest intention of paying him what he asks which is the modest sum of 750,000 francs!!! As further consideration I will send you the photographs Gruel shipped to me and enclose his letter. Will it trouble you very much to return them by registered mail - I will write Gruel that I will do nothing on the matter until I have your opinion

The price of 750,000 Francs is the same as the US$ 150,000 that Voynich would be asking for later. Greene is clear that that is out of the question, but she is sufficiently interested to ask Berenson to go and check it. This two months before the above letter referring to Voynich. Gruel sent photos to Greene, and Greene is forwarding them to Berenson. The later letter refers to photos that Voynich showed someone in London, but it is not clear that the MS is with him at that time.

>>Letter 00227 of 18 February 1913

Greene writes:

Thank you so very much for your letter received yesterday in re Gruel's "Giotto" manuscript - I am so glad of what you say because I had reached almost the same conclusion and it makes me feel so excitedly proud to come within a thousand miles of your opinion, because you know what I think of your opinion - also it encourages me heaps because it makes me feel that perhaps I am learning a bit, if in my old age - so many many thanks - of course I would not pay 1/3 of the amount asked - but if it can be had at a fairly decent price (after you have seen it) I will open negotiations - When you see Gruel don't dismiss the price in any way & then he will not be "down on you" if we dont buy it meanwhile I'll write J. P. M. not to touch it until he hears from me

Unfortunately, we do not find out what exactly was Berenson's opinion, but it cannot have been too bad, because Green was still interested. Possibly, but this is speculation, Berenson was suspicious about the correct attribution to Giotto, which we now know not to be correct. There are hints as to that in the letters, for example the use of quotes and later also questions marks with the name Giotto.

Also, we do not get any indication that Berenson has seen the MS itself with Voynich, so that reference in the March 1913 letter remains a tantalising suggestion that Voynich had these manuscripts already in 1911.

>>Letter 00397 of 17 February 1916

Greene writes:

Voynich came in to see me this morning - He is sailing for England tomorrow to join the army - He had stuck to his price of $150,000. - for his Giotto (??) manuscript & the same amount for the Finiguerra. However when I told him today that I would only have $85,000 to spend on books for the entire year he offered me the Giotto for that sum. Now I cannot make up my mind whether I'd rather have that one or the Finiguerra Do you remember them sufficiently to tell me which one you consider more important?

Leaving aside the inexplicable comment about joining the army, we learn that the price for the MS remains the same, and the Giotto attribution is clearly doubted by Greene. Whether or not her yearly budget limitation of $85,000 is true, this seems like the argument that convinced Voynich to finally sell for $75,000.

The "Finiguerra" is nothing else than another very famous MS that came from the same Jesuit collection, namely the Marcanova that was later acquired by Garrett and is now in Princeton as MS 158. Its illustrations have been attributed to Mazzo Finiguerra (8).

Her question to Berenson demonstrates that she knows that he has seen both manuscripts some time ago, meaning that Voynich must have shown them to him. The only reference for that we have is spring 1911. If Voynich showed him more valuable manuscripts in (say) early 1912, it is hard to imagine that this would not appear in their correspondence.

>>Letter 00398 of 23 February 1916

Greene writes:

Did I tell you that I think of buying Voynich's Italian manuscript the one he attributes to Giotto & which I asked you to look at when Gruel had it? I want the Finiguerra badly but perhaps as a book the Giotto is more necessary for me - Voynich did extraordinary business over here, sold everything he had but those two mss. & made himself exceedingly popular. He has been lecturing at all the Universities Museums & libraries

We see that in her last reference to Voynich she is quite complimentary about him.

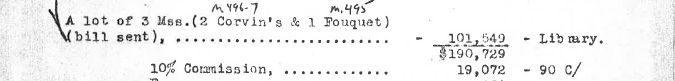

In none of the letters referring to Voynich do we see any mention of the two famous Corvinus manuscripts that were sold to Morgan in July 1912. This was also not to be expected, because the sale did not involve Voynich, but several intermediaries. The special importance of these manuscripts is highlighted here.

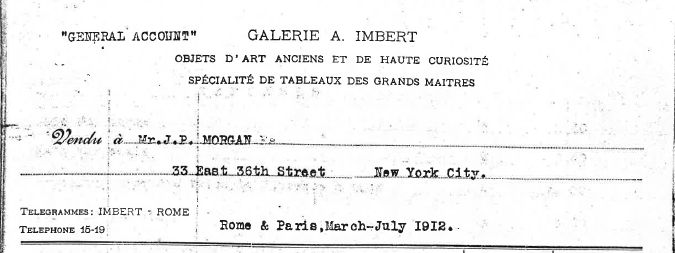

Using several other known names and search terms does not lead us to any direct references. The MS was certainly sold to Morgan by Alexandre Imbert. Copy of the invoice was kindly sent to me many years ago by the Morgan library, and below I show several parts of it.

|

|

|

This tells us that the sale was agreed in March-July 1912, and Imbert addressed the invoice directly to Belle Greene. Indeed, Imbert appears several times in Greene's letters, but this in terms that are anything but complimentary!

>>Letter 00125 of 24 January 1911

This letter predates Voynich's first visit to Berenson. It is the third letter in which Imbert appears, and

in the earlier two she refers to issues that Imbert seems to be having with customs, or the government in

general. Greene writes:

It's what I always felt about them - they rob the people they buy from - they rob the people they sell to and the rob the government - They are now trying to make it hot for Imbert of Rome (whom I loathe) and have been up to see four pictures he sold J.P. - What makes me laugh & cry at the same time is that they are all fakes or rotters - What I call "near" Botticellis, Bellinis etc. The government is grand to J.P. - treats him with kid gloves and the greatest respect & they are now going to quietly appraise them after I had gently but firmly convinced them that the things were absolutely no good & the best one worth at a wild hazard $5000. - so I daresay Imbert will come off easy - of course I only did it to save my adored J.P. any trouble

We must be careful, because it is not always clear who is "they", but there are similar negative comments about Imbert in later letters.

>>Letter 00133 of 21 February 1911

This letter is quite complicated and certainly very important. The single quote of Greene that appears on the

digitisation project's main page comes from this letter. Greene is concerned about various types of dealers of

books and antiquities. She warns Berenson to stay away from them, as these dealers might want to implicate their

relationship in order to obtain a direct line to Morgan, undermining Greene's role. These dealers know that they

would be able to get much more money from Morgan direcly

(9).

She specifically says that these dealers would approach Morgan by going through Imbert in Florence or Rome. Interestingly, that is precisely what is about to happen with the two Corvinus manuscripts.

>>Letter 00149 of 9 May 1911

Greene writes that she is delighted that they will return to Imbert the "near" Bernardino dei Conti ["near"]

Botticelli and the ["near"] Fra Angelico. These terms had appeared before. A similar thing happens again later, in

a letter of 1915.

It is clear that Greene utterly disliked ('loathed') Imbert, but still, there is his invoice of March-July 1912 addressed directedly to her. By searching through her letters from that time span, we only find a few hints:

>>Letter 00203 of 15 July 1912

Greene writes that J.P. [Morgan] is returning on the 24th [from Europe] where he has bought

some A.1 manuscripts. She is eagerly looking forward to seeing them.

>>Letter 00204 of 26 July 1912

Greene writes that she J.P. [Morgan] brought back "a good deal of trash in the way of books with the exception of

one or two good pieces". She adds that Morgan did not like her assessment, but he just has to swallow that.

In the next letters, she is generally unhappy about Morgan, but there is no mention of the Corvinus manuscripts. According to the invoice, these would be shipped (on the Oceanic) on the 31st of August. What seems to be clear is that Morgan made this deal personally, with a person whom Greene loathed and probably would not have trusted, and for an amount of money that she would later call beyond her yearly budget.

This coarse of events is quite surprising, and the correspondence clearly does not provide all there is to know about this deal.

I had hoped to find anything related to Voynich's visit to Berenson, and the manuscripts that he showed him at the time. Fortunately, and rather surprisingly, Berenson wrote to Greene about this, and it prompted Greene to contact Voynich, which then prompted him to write the letter to her. All this is clearly described in the correspondence, down to the wording of the "fine" manuscripts in Voynich's possession.

Furthermore, in the course of subsequent discussions, we find clear indications that Berenson has at some point seen two of the manuscripts that Voynich acquired from the Jesuits, namely his 'Vitae Patrum' with the supposed illustrations by Giotto, and Marcanova's 'Antiquitates' illustrated by Finiguerra. We cannot conclude safely that Voynich already had these manuscripts in July 1911, but we also lack any indication of any other visit, so it remains a distinct possibility.

On the other hand, this relies on Belle Da Costa Greene's correct recollection of which manusripts Berenson had seen, so the information needs to be treated with great care.

The lack of any mention of the two Corvinus manuscripts is surprising. To fully discover what happened here will require additional research, but it seems certain that this deal was made directly between Morgan and Imbert. I cannot escape the feeling that Greene was painfully aware of this direct line by-passing her, and detested it. Morgan had already been purchasing items from Imbert since 1907.

I am only too aware that the above discussion is highly incomplete, as it is based only on the contents of the correspondence, and on a few published books and articles. There is a great amount of additional archival material at the Morgan library (and elsewhere) that would allow for a properly researched publication. It is my hope that this will be undertaken in the not too distant future, by someone more qualified and with better access to the materials.

|

|

|

|