|

|

|

|

This is one of two pages at this site that look more closely at Voynich's acquisition of the Voynich MS. The Voynich MS was just one of several manuscripts he acquired in 1912, and it came from a larger collection of books and manuscripts.

This page explores the details of the 'discovery' of the Voynich MS by Voynich, in particular the two questions where the MS was preserved and how he was able to find and buy it. This work is still on-going, and only one of the two questions seems to have found an adequate answer by now.

The other page explores the composition of this collection. This question is largely answered on that page. There are occasional cross-references between the two pages, but both can be read independently, without having to go back and forth all the time.

There is a third page that paints the historical background of this collection, which is recommended reading, but not absolutely necessary to understand the present page. Some details of that page are also included here.

In all publications about the Voynich MS we read that the location where this manuscript was stored and sold to Wilfrid Voynich was Villa Mondragone in Frascati, but the evidence for this, and for many other details surrounding this 'discovery', have never been analysed in detail. In this page I will investigate two questions: "where was this collection preserved", and "how did Voynich become involved".

In the first part I will present all available evidence related to both questions, first from information presented by Voynich himself, and from other people's reports of his statements. We will see that there are several different versions to his story, in particular about the location of the sale, which is either a castle in Austria, a castle in Southern Europe or more specifically a castle in Frascati.

Following this, I will explore independent sources related to both questions, while keeping open all different versions of Voynich's story. Here, it becomes clear that Voynich was obliged to maintain strict confidence about the sale and about the origin of the manuscripts, by the Jesuit sellers.

Part 3 then concentrates on the question of the whereabouts of this collection. In this area there is important new information, especially from a recent publication that will receive significant attention. Part 4 concentrates on the way how Voynich discovered, or became involved with the collection.

One general conclusion is that Voynich's story that he discovered these manuscripts himself, in chests of which the guardians were unaware of what they contained, is definitely not true. It was a collection hidden by the Jesuits in or before 1873, and eventually offered for sale in 1911 or 1912. Voynich was invited to buy part of it, for reasons that are still partly obscure. The collection was hidden in a Jesuit institution in Castel Gandolfo, not far from Rome.

All books and articles written about the Voynich MS tell us that it was discovered by W.Voynich in Villa Mondragone in Frascati.

Is this really what happened? Voynich always maintained that he discovered the collection of books and manuscripts that included the Voynich MS (1) in chests of which the owners themselves were unaware what they contained, but he never said exactly where this was. In particular, Voynich himself never mentioned Villa Mondragone. This location was announced by Hans P. Kraus thirty years after Voynich's death. Kraus owned the MS after the deaths of Wilfrid and Ethel Voynich, and had access to some information that Voynich had never made public.

This part of the history of the MS has largely been copied between printed and internet sources over the years, without much further investigation, but the availability of new evidence makes this investigation possible now.

Information from Voynich about the acquisition of this collection of manuscripts is relatively sparse. Best known are the statements in his 1921 paper (2), where he refers to his acquisition of a group of manuscipts including his cipher MS in a castle in Southern Europe, while he was keeping the precise location secret, since he was still hoping to buy more books there. This was written nine years after the event, but we also have some earlier statements from Voynich. They are presented here in chronological order.

Our first sources are several newspaper reports from November 1915 that describe a number of exhibitions of Voynich's most interesting manuscripts and early prints (3). I have transcribed them here. These exhibitions included much more than just the collection including the Voynich MS, but the most notorious items came from this collection. During these exhibitions, Voynich spoke about the origin of the collection, and this has been recorded in the above-mentioned newspapers with some variations. Without repeating the full text of the four reports, following is my summary of them.

During research, Voynich found evidence, possibly in some old correspondence, of a collection of manuscripts hidden in Austria. These were manuscripts from ducal or princely libraries, which were taken abroad during Napoleon's invasion into Italy, in order to prevent that they were taken to Paris by Napeolon. After some detective work, Voynich found the chests in a castle in Austria, or a castle of an Austrian nobleman. These chests had not been opened for more than a century, and their owners or guardians had no idea what they contained. Voynich obtained the rights to them, also because the original owners had all died and the collection(s) had been forgotten.

A bit more than one year later, Voynich wrote a letter to Prof. Wilkins of the University of Chicago (4). This letter, which is dated 27 February 1917, was not related to our 'Voynich MS' but to a Boccaccio MS in the University Library, that prof. Wilkins was studying. This MS was previously sold to the library by Voynich. In this letter Voynich answered some questions from Wilkins. The Boccaccio MS originates from the same collection as the Voynich MS (5). The letter says:

The large collection of manuscripts, acquired by me from its hidden place, six years ago, consisted to my best knowledge of many collections belonging to Dukes and Princes, including part of the Malatesta library, part of the Matthias Corvinus library, and part of the Libraries of the Dukes of Parma, Modena and Ferrara, part of the collection of Borso, Alfonso D Arragonia, and several others. I do not know from which of these collections Boccaccio was removed. Until the close of the 18th Century all these manuscripts were in Italy, but were then removed abroad in fear of Napoleon s invasion. As far as I know, from that period until discovered by me, they were not disturbed, and not seen by anyone. The place from which I purchased them I cannot disclose, due to my promise given to the guardians of these manuscripts, whose former owners, as you see, disappeared, thanks to the unification of Italy under the Savoy Dynasty.

In a letter of 18 September in the same year he wrote to Edith Rickert (6), a cryptography expert interested in the Voynich MS:

In regard to the history of the MS., I am sorry I can tell you very little because I am bound by promises made to those from whom I acquired it.

In his 1921 paper (see note 2) Voynich wrote:

In 1912 [...] I came across a most remarkable collection of preciously illuminated manuscripts. For many decades these volumes had lain buried in the chests in which I found them in an ancient castle in Southern Europe

[...]

As I hope some day to be able to acquire the remaining manuscripts in the collection, I refrain from giving details about the locality of the castle.

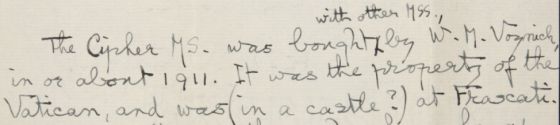

Wilfrid Voynich died on 19 March 1930, and four months later his widow Ethel Lilian Voynich (henceforth simply ELV) wrote a letter that should only be opened after her own death (7):

The Cipher MS. was bought [inserted: with other MSS] by W.M. Voynich, in or about 1911. It was the property of the Vatican, and was (in a castle ?) at Frascati. The intermediary through whom he approached the Vatican authorities was the English Jesuit Father Joseph (?) Strickland, who had, I believe, some connection with Malta. Father Strickland, who has since died, knew that the sale of certain MSS. had been decided upon, if a buyer could be found whose discretion could be trusted. Whether this [inserted: secrecy] was because of the strained relations with the Quirinal I do not know. Father Strickland gave his personal assurance that W.M.V. could be trusted, and on that assurance he was allowed to buy, after giving a promise of secresy [sic]

In 1961, one year after ELV's death, the new owner of the MS was the rare book dealer Hans P. Kraus. From him we have two slightly different reports about a visit he made to the Vatican library, where he spoke about the MS with Mgr. Ruysschaert. This event is described in more detail here.

When I was, a few weeks ago, in the Vatican Library, I found out that the Cipher Manuscript comes from the library of the Collegium Romanum, which was housed in 1911 in the Mondragone Monastery in Frascati. The Vatican Library bought the whole collection and the Cipher Manuscript with the other 17 illuminated manuscripts are still listed in the inventory. This inventory was printed by Ruysschaert Codices Vaticani latini 11414 - 11709.

In 1963 we were in Rome and I visited Monsignor Jose Ruysschaert at the Vatican library. I knew that he had published the catalogue of the Mondragone library and I hoped to get information about the Cipher manuscript.

These two reports from Kraus are not fully consistent: in one the year appears to be 1962 and in the other 1963. Furthermore, in one there is the suggestion that he learned about Villa Mondragone from Ruysschaert, while in the other it appears as if that was his prior knowledge or assumption. In May 1962 Kraus was one of the participants of a trip to Italy that was organised by the Grolier Club (of which he was a member) (8), and the visit to the Vatican Library took place on 22 May. It is clear that the letter to Friedman, written only briefly after the event, must have the correct year. This inconsistency does require us to treat his reports with some care.

There are some common points, and some inconsistencies in the above. What clearly emerges from his own words and actions is that Voynich was only allowed to acquire the set of books and manuscripts under promise of secrecy, and that he always stuck to that.

It is important to keep in mind that this secrecy did not specifically concern the Voynich MS, but the entire collection that he had acquired (see note 1). This is clearly reflected in the above-mentioned letter about the Boccaccio MS of the University of Chicago (9). His secrecy is confirmed by material now preserved in the Beinecke Library. Some of the documents have comments written in pencil saying "safe to keep" or "don't destroy this" (10), showing that other material must have been destroyed.

The year in which Voynich 'discovered' the MS is traditionally reported as 1912, and this is the year that he mentioned in his 1921 publication. On the other hand, the letter from ELV (see note 7) says "1911 (or about)", and the 1917 letter from Voynich to Wilkins says "six years ago", implying 1911. Kraus' letter to Friedman also mentions the year 1911. Finally, Ruysschaert (1960) (11) writes "towards 1912" (from his French: "vers 1912"). We cannot yet resolve this uncertainty, and it will be safer to write 1911-1912. It is of course quite possible that his involvement in the acquisition spanned the years 1911 to 1912.

The main inconsistencies in the various reports from Voynich are the following:

What further complicates matters is that Voynich was a man with a very lively fantasy. This was already pointed out by Rafal Prinke (12), and we find more proof of it in Kennedy (2016) (13). Both aspects have been reflected in Voynich's biography: we find that he loved to exaggerate both the details of his life (for example claiming that he wandered through a Mongolian desert for months) and the details of his books (claiming that they should have illustrations from the hands of such famous artists as Giotto and Mantegna) (14).

In view of all this uncertainty, let us not try to jump to conclusions now, but look at evidence that is independent of what Voynich said or did. After that we can address the two main questions: "Where was the collection preserved?" and "How did Voynich obtain access to it". The third question about the reasons for Voynich's secrecy will be dealt with after that.

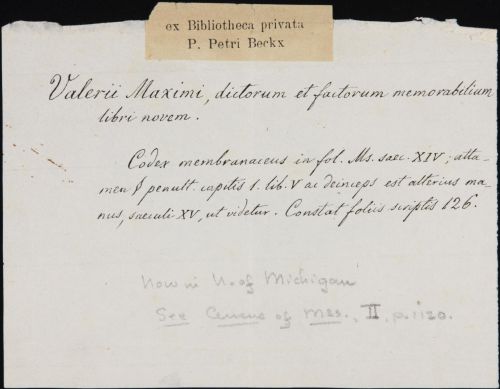

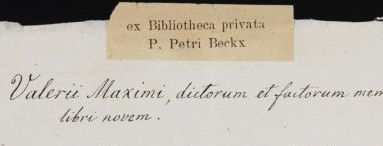

The manuscripts that Voynich acquired had bibliographical paper slips attached to them, which he removed and kept under wraps. They were found in the London shop by Herbert Garland in 1937, sent to Anne Nill in the US and are now preserved in the Beinecke Library. As far as I know, Voynich never mentioned or showed these to anyone. An example of these bibliographical slips is shown below.

The small typewritten sticker attached to this bibliographicl slip says: ex Bibliotheca privata P. Petri Beckx and this points directly to the origin of this collection. Petrus Beckx S.J. was the Superior-General of the Society of Jesus when the Jesuits' posessions were confiscated in 1873. These paper slips are discussed in a dedicated section in the parallel page, with an additional short analysis here. That analysis shows conclusively that the collection of manuscripts, from which Voynich was allowed to acquire a subset, originally belonged to the Society of Jesus. At the same time, the earlier princely and ducal owners of these manuscripts, whom Voynich mentioned on several occasions, were not an invention. These were the owners of the manuscripts before they entered the Collegium Romanum Library, and another section of the parallel page shows that each of the names in Voynich's letter to Prof. Wilkins (as cited above) is attested.

The remaining (larger) part of the collection was acquired by the Vatican library. Vatican printed sources (15) record that this happened in 1912, while Franz Ehrle S.J. was prefect of the library. As explained in detail on the parallel page, the Latin manuscripts from this collection are now preserved there as Vat.Lat.11414-11615, and these also include the same bibliographical notes with stickers referring to P.Beckx.

Events following the confiscation of Jesuit possessions in 1873 have been described in detail in the historical background page and can just be summarised here.

The collection of manuscripts that we are interested in, disappeared from sight around 1870-1873, when the libraries of the Society of Jesus were confiscated. Three of the manuscripts that originate from this collection, and were acquired by Voynich, had been consulted in the Collegium Romanum library before this event (16), and for two of them, namely two manuscripts that originate from the library of Mathias Corvinus, their disappearance has been recorded by contemporary sources. The special case of these two manuscripts is discussed in more detail further below.

A letter by the Jesuit Father Paul Pierling (1840-1922), who witnessed the events in the Casa Professa, clarifies that possessions of the Society of Jesus should be confiscated, but private possessions of individual Jesuits, including books, should remain theirs. This provides a plausible explanation for the 'Private library of P.Beckx'. It was almost certainly a ruse which allowed the Jesuits to preserve books from their libraries from confiscation by the state. In Carini Dainotti (1956) (17) we read that Beckx was formally allowed to keep 4000 books related to theology, church history and philosophy. In addition, she writes, P.Beckx took 60 cases out of the Casa Professa.

The main library of the Collegium Romanum was confiscated, which means not only the books, but also the building itself, which was simply converted into the new state library. One important collection was hidden inside this building. This collection of books and manuscripts was stored in a room that has become known as the Ripostiglio which was locked and hidden behind a trap door (18).

It was discovered in 1877. The most important manuscripts in this collection were transferred to the state library where they now form the Fondo Gesuitico. None of the manuscripts from this collection had a "P. Beckx" sticker attached to it. The most valuable item was a Muretus autograph, but it also included five autograph manuscripts of Kircher. This clearly shows that Kircher's library had been integrated into the Collegium Romanum library by then.

Petrus Beckx, the general of the Society of Jesus, was also responsible for securing another important library from confiscation by the Italian state, namely the library that was known at the time as the library of the Duchess of Sachsen. Nowdays, it is more generally known as the Bibliotheca Rossiana (19). More details about this may be found on in the historical background page (here and here). In order to avoid dispersal of this collection of her late husband de Rossi, which counted over 10,000 items, the Duchess donated it to the Jesuits in Rome, who stored it in the Casa Professa. This donation was governed by a formal contract, signed by herself and by P. Beckx, which stated among others that, in case the Jesuit order were ever completely dissolved, the next rightful owner of the library will be the Emperor of Austria. When the newly formed Italian state confiscated all libraries owned by the Society of Jesus, for the library of the Duchess, who had already died in 1857, this clause in the contract had come into effect, and the Austrian ambassador to the Vatican agreed with P.Beckx that the entire collection should be transported to Austria. Eventually, in 1895, this collection was moved to the Jesuit College in Vienna's 13th district: Wien-Lainz. At this time it contained approximately 9000 items, including about 1200 manuscripts, 2500 incunables and some 5300 mostly valuable later prints.

In 1912 there was talk of selling this library, and both antiquarian book dealers (20) and major European libraries were interested, but this sale did not take place because of legal concerns related to the contract of the Duchess with the Jesuits. Finally, in December 1921, the entire collection was moved from Vienna to the Vatican, and incorporated into the Vatican Library as the Fondo Rossiano, where the books and manuscripts received new shelf marks, and where they are still preserved today. This transfer involved difficult negotiations, since the Italian state was still very interested in Jesuit property that they considered subject to confiscation. This is nine years after the sale of the Jesuit collection that included the Voynich MS, and it clearly shows that the confidentiality of that sale in 1912 was justified.

In a newspaper article from the Journal de Lyon of 29 October 1873 (cited and transated here), we read that 144 Jesuits had to leave Rome. 50 of them moved to two Villas that the prince of Torlonia had placed at their disposal: one in Castel Gandolfo, the other on the ancient territory of Bola, between Praeneste and Tivoli (21). Several were accepted at the college of Mondragone, in Villa Borghese in Frascati. We read in the biography of Beckx (22) that the prince Alessandro Torlonia was a close friend of Beckx and a great supporter of the Jesuits, and when, on 13 October 1873, the historical Jesuit novitiate of St.Andrea al Quirinale was forced to close and had to be evacuated within two weeks, he immediately offered to continue the activities in his Villa in Castel Gandolfo.

Finally, we read in the preface of Chan (2002) (23):

The authorities of the Order made an attempt to save the Archives from any harm. They were first transferred to the basement of the Palazzo Torlonia on Via della Riconciliazione (24) and in 1873 to the attics of the German College which at that time was located in the Palazzo Borromeo on Via del Seminario near St. Ignatius Church.

It is clear that Prince Alessandro Torlonia (1800-1886) played a significant role in helping the Jesuits in 1873.

The manuscripts described throughout this page can be subdivided into three groups, and all are identified by the stickers referring to P.Beckx, which may be found:

Examples from all three groups are shown here.

All of these documents were originally preserved in the Collegium Romanum library (Bibliotheca Maior). This is further confirmed by the the original Collegium Romanum shelf marks that they occasionally still bear. They have been written in pencil on the reverse of the bibliographical slips of the first two collections. See for example "4 c 62" in >>MS Vat.Lat.11543 ), with similar codes (4, followed by a character c-f, followed by a number) on many of the Beinecke slips. A few are also written in the margins of the 1903 catalogue, and Ruysschaert mentions them in the preface to his catalogue.

These codes match the type Se >>as discussed on this page. In addition, in van Mater Dennis (1927) (25) we read that the Marcanova MS of the collection bought by Voynich was seen in the Collegium Romanum library, with shelf mark "4 F 44". Another MS that was acquired and sold by Voynich was seen in 1870 by the Hungarian historian Flóris Rómer, who reports that it had shelf mark "4 f 45" (26).

Several tentative locations where the collection may have been hidden were mentioned above. As a result of the discovery of new key evidence, just a brief summary of these will be sufficient.

Voynich initially claimed that the collection had been stored in a castle in Austria. This is a tempting option, given that, indeed, P. Beckx preserved another collection of books in a Jesuit house in Vienna, namely the library of De Rossi. This collection ended up in a former Jagdschloss so it would be justified to call it a castle. However, Voynich later changed this to a castle in Southern Europe. Probably his most credible story is what he told his wife in confidence, which is "Frascati". While the option of a castle in Austria has been analysed in detail in previous versions of this page, there is no more reason to maintain all this analysis here.

Hans P. Kraus' statement that the MS had been preserved in Villa Mondragone is at least consistent with the evidence in the letter by ELV (27), and this location has always been considered the most certain aspect of Voynich's acquisition of the MS. While researching this part of the history of the MS I have not been able to find any confirmation of this, and began to doubt it. This was strengthened by the opinion of researchers of the history of the Jesuits, with whom I have been in contact in recent years. The support that Beckx and the Jesuits obtained from Alessandro de Torlonia made one of his villas, especially one in Castel Gandolfo, a viable alternative.

When, in 1886, the Jesuit bibliographer Carlos Sommervogel was compiling his new version of the complete Jesuit bibliography (28), he realised that important references for him were contained in the hidden archives of the Society. He temporarily obtained access to some documents in these archives, and from this episode we know that they were stored somewhere in the Roman province (29). His new issue of the Bibliothèque de la Compagnie de Jésus (30) started appearing in 1893. This huge bibliography does not mention the Carteggio Kircheriano, which consists of 14 volumes now in the Fondo APUG and with the typescript label Ex bibliotheca privata P.Petri Beckx. The Jesuit bibliographer Sommervogel did not know about their existence!

As regards the collection of 380 manuscripts acquired by the Vatican (and Voynich), the Jesuit historian Miquel Batllori S.J. declared many decades later, in 1962 (31), that he had not been able to find any detail about the sale of the manuscripts to the Vatican library, or about their previous whereabouts, despite searching for it in the Roman Archives of the Society (ARSJ). These two points show on the one hand that archive material was stored somewhere in the Roman province, but on the other hand that the items labelled as from the private library of P.Beckx were indeed completely hidden from sight, even to Jesuit historians and researchers.

In a recent publication (32), Francesca Potenza of the University of Palermo presents and analyses a significant amount of new evidence. In this she was supported by earlier work of Lorenzo Mancini, then working at the Historical Archives of the Pontifical Gregorian University (APUG), the same archives that preserve the Kircher correspondence. The following summary also includes some information that was already available before this publication.

In or before early 1912, the Jesuits created two catalogues of books and manuscripts, that are now preserved in the above-mentioned Gregorian Archives. The first (APUG 3225) bears the comment: "Catalogo dei MMSS. dell'Archivio della casa di Castel Gandolfo appartenente all'Università Gregoriana" or: "Catalogue of manuscipts of the archive of the house at Castel Gandolfo belonging to the Gregorian University". This catalogue lists the manuscripts that are now preserved in the Gregorian Historical Archives (Fondo APUG), of which most have a sticker referring to the private library of P.Beckx. The second (APUG 3289) is the original of the document Arch.Bibl.109 that was already described and discussed in some detail on the parallel page. This original was rediscovered as recently as July 2019 by Lorenzo Mancini. Both catalogues use the same layout and the same material, and they were evidently created at the same time, describing books and manuscripts preserved at the Villa Torlonia in Castel Gandolfo.

Potenza then introduces and analyses two documents from the Vatican archives that contain newly discovered information related to the sale of these manuscripts. The first (33) includes three letters from the Father Provincial of Rome: Augusto Spinetti S.J.

Spinetti's Letter 1 is addressed to the prefect of the Vatican Library Franz Ehrle S.J., and is dated 12 June 1912. In this letter Spinetti informs Ehrle that he has spoken with Pope Pius X about selling some Jesuit manuscripts. The reason for the sale is explained: this is out of financial needs. Ehrle is invited to come and visit, in order to make an estimate of the price. Spinetti adds that they already have an offer of 500 Lire per item.

In letter 2, written 5 days later, Spinetti informs Ehrle that the place to inspect the manuscripts is in the Jesuit house in Castel Gandolfo. He adds that Ehrle needs to present some pretext for his visit, because nobody (beside the highest-placed officials) knows about the true reason for his visit. He will be accompanied by father Pietro Tacchi Venturi of the Society of Jesus.

Letter 3 was written on the same day as letter 2, but to the above-mentioned Pietro Tacchi Venturi. In this letter he adds that the Jesuits already have an offer for the collection of 100,000 Lire. Comparing this with the first letter shows that the offer they already have was for 200 manuscripts, or at least approximately.

Potenza also found an entry in the house diary of Villa Torlonia at Castel Gandolfo (34) that Franz Ehrle and Pietro Tacchi Venturi visited the place together on 24 June 1912, one week after the above-mentioned exchange of letters.

The second archival document (35) includes a letter dated 8 July 1912, from father Ehrle to Mgr. Bressan (36) asking the latter to inform the Pope that his price estimate is 50,000 Lire and that it is clear from his visit that after the sale the greatest discretion will be necessary. The pope answers in his own hand to proceed prudently and silently (37). A few days later, on 13 July, father Ehrle writes that the 50,000 Lire have been paid to the Jesuits, and that 12 or 13 cases (casse o cassette) have arrived from Villa Torlonia.

Furthermore, Potenza shows that the collection selected by Ehrle included the autograph manuscripts of the Jesuit professor Girolamo Lagomarsini (1698-1773). For these nearly 100 manuscripts he estimated a separate price of 5000 Lire. They are equally described in Ruysschaert's catalogue as Vat.Lat.11617-11707. However, these manuscripts are not listed in APUG 3289, but in APUG 3225, suggesting that they were not originally considered to be sold to the Vatican. This clearly shows that the two collections described in these catalogues were kept together in the Villa Torlonia in Castel Gandolfo.

From all of this, combined with the title of MS APUG 3225, it is certain that the Jesuit collection of manuscripts from the Collegium Romanum, that was salvaged from confiscation by the Italian state, was preserved in the Villa Torlonia in Castel Gandolfo, until it was sold to the Vatican library, and in part to Wilfrid Voynich.

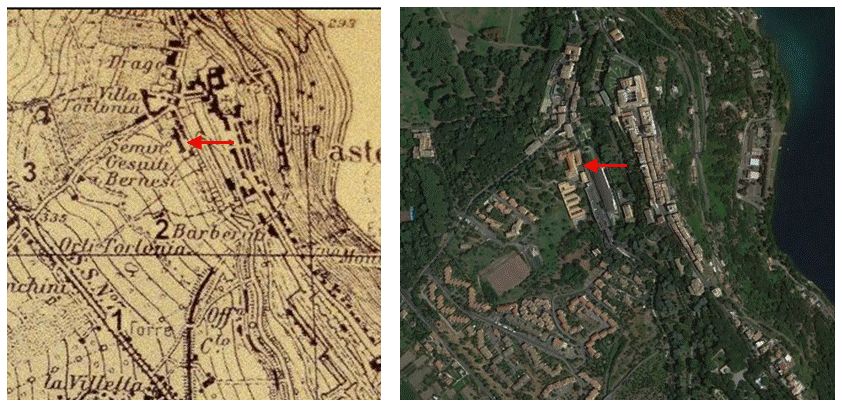

As mentioned above, prince Alessandro Torlonia (1800-1886), a close personal friend of Petrus Beckx, helped the Society of Jesus in 1873 by hosting people, a school and Jesuit documents in the various dwellings he owned inside and outside Rome. In particular he invited Beckx to stay in his Villa in Castel Gandolfo, which would also host the Novitiate, after the original site in Rome was forced to close. This now also turns out to be the site where the manuscripts of the Collegium Romanum were preserved. So where is this Villa?

In literature, two such buildings are mentioned. One is known as Villa Carolina, also occasionally Delizia Carolina, and the other as the Villa dei Gesuiti. Both were acquired independently by Giovanni Torlonia (1755-1829), and inherited by Alessandro's older brother Carlo. Upon Carlo's death in 1848 they both befell to Alessandro. The building in which Alessandro agreed to host the Jesuit novitiate was the Villa dei Gesuiti, which derives its name from the fact that in the past it had belonged to the Society of Jesus. It was, however, taken from them in 1773 (38). A photograph of the building, made before 1902, is shown below (39). The publication of Potenza includes a different photo of the same building, and additional illustrations related to the Villa.

Its location both on a map of 1913 and a modern satellite view is shown below.

Both Villas are visible in the aerial picture below.

The manuscript collection acquired by the Vatican was sent directly from Castel Gandolfo to the Vatican, as demonstrated by the letter from Ehrle announcing the arrival of the 12 or 13 cases. Is there any chance that the manuscripts that Voynich acquired were stored in Villa Mondragone? Francesca Potenza also analyses the same question in her publication, and the only possibility is that, perhaps, this smaller group of manuscripts was temporarily moved from Villa Torlonia to Villa Mondragone during the sale to Voynich. However, when the catalogues were composed, the manuscipts that Voynich acquired were not described separately, but appear scattered among the largely alphabetical list, so at this time the manuscripts were all together in the same place: Villa Torlonia. The only reason to maintain the option of Villa Mondragone is ELV's mentioning of Frascati, which is certainly distinct from Castel Gandolfo. We will come back to this question while we analyse Voynich's involvement in this sale further below. There is, however, another piece of evidence pointing to Frascati, yet not to Villa Mondragone.

There is a third location that presents itself, and this derives from a remark made by Tammaro de Marinis, Italian bibliophile (40), who became intimately involved in Voynich's deal with the Society of Jesus right from the beginning. Seven of the manuscripts that Voynich acquired from the Jesuits were immediately passed to him, and appear in his 1913 sales catalogue (41), including two extremely valuable Corvinus manuscripts.

As shown in the parallel page, his 1913 catalogue does not mention Voynich at all, which is consistent with the secrecy that must have also governed the agreement between them. However, in his 1947 / 1954 work, written many years after Voynich's death, he clearly states that he obtained two of the manuscripts in that catalogue from Voynich. He seems to have decided that this was no longer a sensitive piece of information. Interestingly, he also writes that these books originate from the collection of: "Henry Benedict Stuart, Cardinal of York, Bishop of Frascati, passionate collector of manuscripts, which was left to the bishopric".

This is clearly not correct, because we know for certain that these manuscripts were in the Collegium Romanum library. Their bibliographical slips have been preserved and they appear in APUG 3289 / Arch.Bibl.109. The catalogue of the Duke's library has been published (42) and it does not contain any manuscripts with these two titles. However, the library of Henry Benedict Stuart might not refer to the collection of books, but rather to the location (building). The latter can be identified with certainty, and is an annex to the Gesù church of Frascati, as shown below.

Let's analyse the possible accuracy of this information. De Marinis felt at liberty to divulge the information, secret until then, that he obtained these books from Voynich. This means that this is highly unlikely to be an invention to avoid telling the truth. It is more likely what he believed to be the truth. Now Voynich had told ELV that the manuscripts were in Frascati, but that information could not yet have reached De Marinis in 1947/1954 as ELV's letter was only opened in 1960. Therefore, it appears to be a second more-or-less independent identification of Frascati as the location of hiding. The "more-or-less" is due to the observation that both probably derive directly from Voynich. It is of course entirely possible that Voynich decided not to tell the whole truth to De Marinis (and to his wife), but all we can do is speculate about this.

The location in Frascati does not necessarily have to be a castle, because in ELV's letter (above) she puts a question mark after the word "castle", indicating that she is uncertain about this, and it may merely be a consequence of Voynich mentioning a "Castle in Southern Europe" in his 1921 presentation.

This new suggestion is certainly highly speculative, and the experts who should have the best knowledge about these events, namely the historians of the history of the Roman Jesuits, and the author of the publication of the Duke's library catalogue, have no evidence and are highly skeptical about this hypothesis (43).

Finally, the house diaries of Villa Torlonia and Villa Mondragone do not have any record that Wilfrid Voynich ever set foot in either place (44). Joseph Strickland, on the other hand, appears several times in the records of both houses.

How did Voynich obtain access to this valuable collection? He presented two explanations. Initially, he claimed that he discovered the collection himself, in a place that was completely forgotten by the owners. Later, he argued that he was given the possibility under promise of complete secrecy. The first option is highly unlikely, especially since he argued that these previous owners were Italian nobility who moved their manuscripts to Austria to avoid them being taken by Napoleon, and the chests had not been opened for more than a century. This reads like a fairy tale, and does not fit any of the other evidence. The second option is much more likely, as it is also what he told his wife in confidence. She added the detail that this was thanks to the intervention by a Jesuit called Joseph Strickland, about whom more will be said below. It is also consistent with the evidence presented above. The question of secrecy is dealt with conclusively in Section 5 below.

What we already established above is that Voynich ended up competing with the Vatican Library (whose prefect was also a Jesuit) over some manuscripts owned by the Society of Jesus, in a sale that had to be kept secret, because there was a high risk of confiscation of the collection by the state. We may find out more about the sequence of events by following the fate of a pair of extremely valuable manuscripts from the library of King Matthias Corvinus.

The famous humanist library of King Matthias Corvinus of Hungary, its destruction and the dispersion of its books in the first half of the 16th century, has been a topic of great historical interest, especially for Hungarian researchers.

In 1867, a librarian of the Roman Casa Professa wrote to the Hungarian historian and priest Vilmos Fraknói that his library contained a collection of books of the Duchess of Sachsen (45), which should be sent to the emperor of Austria, and this collection included a MS originating from king Mathias Corvinus (46). This prompted the historian Flóris Rómer to travel to Rome in 1871 and take photographs of a set of four Corvinus manuscripts known to be in Rome. These photos were published in Rómer (1871) (see note 46), and concerned the aforementioned MS (a missal) in the library of the Duchess, a breviarum preserved in the Vatican library (47), and two manuscripts in the Jesuit library in the Collegium Romanum: a Cicero MS and a MS of Didymus Alexandrinus and other texts.

This publication written in Hungarian became well known among historians in Hungary, but appears to have been hardly known outside. One of the two manuscripts in the Collegium Romanum contained what was judged to be the most life-like extisting portraits of the King and his wife, Queen Beatrix (see below, or see >>here for modern digital scans).

It prompted later researchers of the library of Corvinus to search for these manuscripts in Rome, but they went in vain: János Csontosi in 1886 (48) and Wilhelm Weinberger in 1908 (49), are two examples known to me. The latter reported that he had gone to see the missal in the Vienna Jesuit college, which was also mentioned above. He wrote that the other two from the Collegium Romanum, like many other books from the Collegium Romanum, should have been moved to the Vittorio Emanuele library in Rome. However, they were not to be found there, and must be considered lost.

Next, in 1912, these two manuscripts surfaced in Hungary, where they were offered for sale by the Florence book dealer Tammaro De Marinis (see note 40). There, these manuscripts were recognised immediately, and the historian and politician Albert De Berzeviczy was greatly interested in acquiring them. On 26 June 1912 he gave a lecture about the importance that these two manuscripts returned to Hungary. Also this lecture was published in Hungarian only (50). However, already by July 1912 these two manuscripts were sold to Pierpont Morgan through one of his favourite dealers in Rome: Alexandre Imbert. De Marinis' partner Vittorio Forti remembers these details in a letter to H.P. Kraus in 1975 (51). Forti writes about his trip to Hungary, where the archbishop had hoped to raise the money to buy these books. The archbishop was none other than Vilmos Fraknói, who had been informed about these manuscripts 45 years earlier, as mentioned above! Forti also writes that these manuscripts came from Wilfrid Voynich and they paid him 300,000 Lire for the pair.

If we compare the dates above with those of the interactions between the Jesuits and the Vatican Library, we see that these two manuscripts had already passed from Voynich to De Marinis, and subsequently been taken to Hungary, before Franz Ehrle informed Pope Pius X of his price estimate. This means that Voynich had been given the opportunity to acquire these manuscripts before the Vatican Library! This also strongly suggests that the person making the offer of 500 Lire per volume, or 100,000 Lire for all 200 of them, would have been Voynich.

On the other hand, the catalogue APUG 3289 clearly refers to a manuscript sale to the Vatican, and the list includes those manuscripts that Voynich acquired. Based on this somewhat contradictory evidence, we can only speculate about the exact sequence of events and the reasons for Voynich's involvement. Still, the Jesuits must have been aware of the great interest in these two Corvinus manuscripts, based on the efforts of Hungarian researchers over several decades to find them, and the newly found evidence also clarifies that the reason for the sale by the Jesuits was a financial one.

We have some insight into father Ehrle's acquisitions of manuscripts from a German publication from his hand, written just a few years after this sale (52). He explains how difficult it is to estimate the value of any manuscript library, due to the individual value of each and every item. Using the example of the acquisition of the Borghese libary that was initiated in 1891, he explains that his method is to divide all books into a few different classes based on their perceived artistic and scientific value (from high to low), and to estimate a value of each group separately, taking into account the number of items it includes.

He also explains that the price to be offered for the collection depends very much on competition from other potential buyers. The best case, he says, is when only Roman antiquarian book dealers are interested. It gets worse when there is an interest from private collectors, Roman scientific institutes, foreign antiquarians or institutes, or even governments. Ehrle presents similar arguments in his above-mentioned letter to Mgr. Bressan.

The Borghese library, which included a manuscript collection of around 400 items mainly on parchment, was finally sold to the Vatican for 210,000 Lire. The very important library of the Barberini, of which Ehrle estimated the value at 750,000 Lire, was sold to the Vatican for a bargain 500,000 Lire. What appears clearly from this publication more in a general sense is, that the budget of the Vatican library was limited, and there was a need also for them to negotiate.

While the Vatican paid 50,000 Lire for the collection, we know from the letter of Forti mentioned above, that Voynich was paid 300,000 Lire (by his buyer De Marinis) for 'just' the two Corvinates. Of course we don't know how much Voynich paid the Jesuits for them, but it is clear that the commercial competition in this case must have been overwhelming.

From the correspondence discovered by Potenza, it would appear that the Jesuits lost a large amount of money by selling to the Vatican instead of Voynich. However, from the correspondence of Ehrle it also appears very clearly that it would have been far too risky to sell the complete set to a private dealer. Ehrle even instructs the Vatican library that extreme care must be taken to avoid that the Vatican will be targeted by the government, for hiding these volumes.

The Jesuit father Joseph Strickland (53), who was the intermediary for the sale according to ELV's letter, was an alumnus of the nobile collegio Mondragone. From 1903 to 1911 he was working in Florence (54), where Voynich was operating one of his book stores since 1908. Some letters from Joseph and Paul Strickland (Joseph's brother, also alumnus of Villa Mondragone), written shortly after the sale of the manuscripts to Voynich, are preserved in the Beinecke. They have been transcribed here. The first letter, dated 26 June 1912, includes a reference to the Roman Provincial father Spinetti, and also says that there is a letter from Spinetti for Voynich. This is after Voynich had already obtained the two Corvinates (these were in Budapest on the very same day, as we had seen above), and it coincides exactly with the time when Spinetti was interacting with the Vatican about the sale of their manuscripts (see Section 3.2).

While this is the first independent indication of Strickland's mediation between Voynich and the Jesuits, an even stronger example is found in the last letter, dated November 1913, where Strickland writes:

For various reasons, the 200 items you heard of, are no more at the disposal of our friends. Something else may turn up later on, but not for the present.

It is hard to conclude anything other than that this is a reference to the 200 volumes for which the Jesuits had received an offer of 500 Lire per volume, before the Vatican was asked to make a bid. These volumes were then sold to the Vatican in July 1912. An annotation on the first letter in what could be Voynich's hand clarifies that other correspondence with Strickland must have been destroyed. The letter from Spinetti has not been found in Voynich's material preserved in the Beinecke, so this is rather likely to be one of the victims. Furthermore, two of the letters from the Strickland brothers have a Villa Mondragone letterhead. We may only surmise that it was on this basis, combined with the mention of the '(castle?) at Frascati' by ELV, that Kraus wrote to Friedman that the location of the sale was Villa Mondragone.

While Kraus' letter seems to suggest that he might have obtained this location from Mgr. Ruysschaert, this is almost certainly not the case. All evidence, both from Ruysschaert's catalogue, and information presented by Potenza, shows that Ruysschaert did not know where the manuscripts had been preserved, and even if he did, he would have known that this should remain a secret.

The last letter from Strickland also informed Voynich about the new strict laws related to exportation of art treasures from Italy (55), which clearly applied to the manuscripts he acquired.

The easiest argument to make is that of the need for secrecy, as we encounter this everywhere. Voynich gave two possible reasons for his secrecy. The first was that he was obliged to maintain secrecy about the sale by the guardians (i.e. sellers) of the manuscripts. The second, later reason was a commercial one, namely that he was still hoping to return to this place to buy more manuscripts. ELV mentioned the need for secrecy in her letter to be opened after her death. Voynich also mentioned his promise of secrecy in his 1917 letter to prof. Wilkins of Chicago.

We have even more independent evidence of this secrecy. As mentioned on the parallel page, in the manuscripts preserved in the Vatican the name of Beckx has been erased, while on the slips we still have from Voynich it is perfectly legible. This is demonstrated below.

This means that the erasure was not done before the sale, but by the Vatican library after the sale. This need for the Vatican to hide the origin of the manuscripts tells us that the entire sale must have been done in confidence.

The publication by Francesca Potenza provides even more direct evidence, as we already saw above. In letter 2 of Spinetti to Ehrle he clearly indicates that the purpose of Ehrle's visit is a secret to be kept even among Jesuits. In Ehrle's letter to Mgr. Bressan he also reiterates this need for extreme discretion. Potenza furthermore adds that in the Greek manuscripts that were sold to the Vatican, the stamp referring to Pope Pius' donation has been erased, something that was not done for the Latin manuscripts.

Finally, we saw that even ten years later, when the Bibliotheca Rossiana was transferred from Vienna to the Vatican, great discretion was still required.

However, the case of the two Corvinus manuscripts shows that this secrecy was very difficult to maintain. In De Marinis' 1913 catalogue he never mentions Voynich or the Collegium Romanum, but there are references to two Hungarian papers that would allow anyone to realise that this is where these manuscripts came from. But this seems not to have happened.

In (or before) 1873 two collections of manuscripts were removed from the Collegium Romanum library, and hidden in the Villa Torlonia in Castel Gandolfo. The reason for this transfer was that the newly formed Italian state had issued a law of confiscation of libraries, and they were particularly interested in the Collegium Romanum library of the Jesuits.

In or before 1912 two separate catalogues of these collections were made, where the smaller collection of 'old' manuscripts (including the Voynich MS) was offered for sale. The reason for this sale was a need for money by the Jesuits, as their regular source of income from their institutions had been reduced severely by the confiscations by the Italian government.

By June 1912 some of these manuscripts had already been acquired by Wilfrid Voynich, apparently through the intermediation of his Jesuit friend Joseph Strickland. In the same month, the prefect of the Vatican library was invited to make a price estimate for the remainder. For this purpose he visited the Villa Torlonia on 24 June. For the agreed price of 50,000 Lire these manuscripts were transferred from Castel Gandolfo to the Vatican in July 1912. They were acquired by Pope Pius X and donated by him to the Vatican library.

While father Strickland was based in Villa Mondragone near Frascati, there is no evicence that the manuscripts acquired by Voynich were ever inside the Villa.

The entire sale had to be executed under complete secrecy, as the Italian government still considered these manuscripts their property. Voynich only told his wife (ELV), in confidence, who wrote this information down in a letter that was opened 30 years later. While there is no reason to think that ELV deliberately provided any misleading information, some of the details turn out to be only partly accurate.

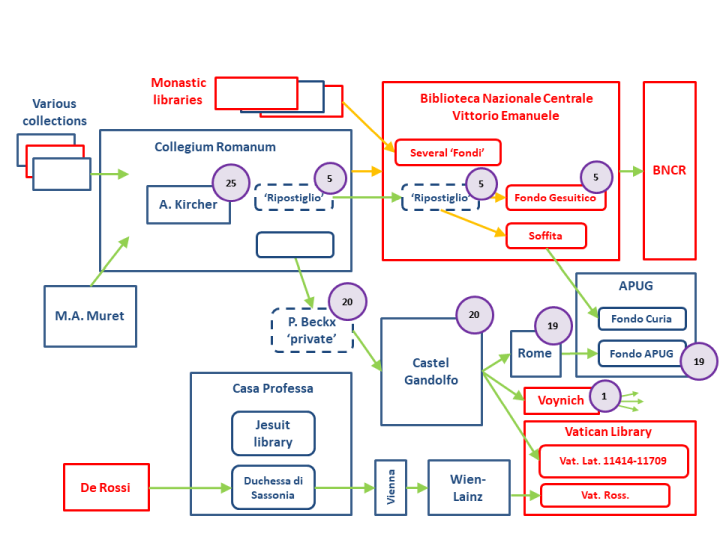

Following is a graphical representation of the various moves of Jesuit library material. In this illustration, blue boxes refer to Jesuit collections and red boxes to other collections. Orange arrows are 'involuntary' moves, typically confiscations. Items that trace back to Athanasius Kircher have been enumerated in purple circles, because he was the last owner of the 'Voynich MS' and it almost certainly passed to the Collegium Romanum library after his death. A group of 19 of his manuscripts, including his complete correspondence but also some other autographs, is now preserved in the Fondo APUG in the historical archives of the Gregorian University. Another 5 Kircher manuscripts are now preserved in the 'Fondo Gesuitico' of the national library of Rome

|

Vicissitudes of the Society of Jesus. |

Voynich initially claimed that his collection of manuscripts was discovered by him in Austria, after it had been moved there from Italy long before. This version of his story appears to be a consequence of the warnings by Strickland about the strict laws related to exporting art treasures from Italy.

Later, he changed his story from an 'Austrian castle' into a 'castle in Southern Europe'. Ellie Velinska has a plausible explanation for this. In 1917, Voynich had been denounced and become a target for investigations by the FBI, because he had been talking freely about obtaining manuscripts with secret codes in Germany and Austria, during the time of World War I (56). Because of this, not only he, but several other people in his circle were investigated. It must have seemed a good idea to move away from Austria, and just say 'Southern Europe' (Italy still not being safe).

In 1921 he argued that his reason for secrecy was that he was still hoping to go back to the source and acquire more documents. This is an argument that book dealers would understand, and the last preserved letter from Strickland indeed hints at this possibility. Of course, the true reason was that he was not allowed to talk about it, but publicly hinting at a promise of secrecy is counter-productive to this secrecy as it raises suspicions.

We still do not know how this sale started. Both Voynich and the Vatican were already involved before the first letter from Fr. Spinetti to Fr. Ehrle of June 1912. However, we do not know how long before, and in which order they became involved. Voynich and the people near him mention the year 1911, and this fits with the time frame in which Voynich could have first met Strickland.

What puzzles me most, personally, is the question how Voynich was able to select the manuscripts that he acquired. There are two possibilities.

The first is that he could see them and make the selection personally. This fits with his descriptions in his 1921 publication, which, of course, have turned out not to be true in many respects. In this case, he would have had to enter the Villa Torlonia in Castel Gandolfo, or the manuscripts would have had to be taken out for a short time, for him to see. Given the great care taken for Ehrle's visit to see the manuscripts (and Ehrle was himself a Jesuit!) both seem very unlikely. There is no record of Voynich entering the Villa in its house diary (57).

The second possibility is that he relied entirely on the advice of Joseph Strickland, who could see the manuscripts. What are probably the two most valuable manuscripts: the Didymus and the Marcanova, do not appear in the Jesuit list of books for sale to the Vatican, and both were obtained by Voynich. Essentially all other books that Voynich obtained can be found in this list. Even though it does not play any major role for our understanding of the events, I am tempted to consider that these two manuscripts had been foreseen to be sold to Voynich from the beginning. He would have been given them by Strickland, with the bibliographical descriptions already removed (58). He may then have negotiated with Strickland (or rather, with the Jesuits through Strickland) about additional books that he would acquire, and in the course of this made his offer of 500 Lire per volume. The Cicero, also coming from the library of Corvinus, must have been available to him early enough for De Marinis to take it to Budapest. This volume appears in APUG 3289 / Arch.Bibl.109 and its bibliographical slip was preserved by Voynich and is now in the Beinecke library.

Potenza (59) records that Strickland visited the Villa Torlonia on 25 and 29 April 1912. While there are no details, these dates are compatible with the time frame of the selection and acquisition of the manuscruipts by Voynich. In this scenario, Strickland would have taken the books with him, and Voynich could have received them from him in Frascati, not necessarily inside the Villa Mondragone (see note 57).

There are too many possible scenarios why ELV ended up mentioning Frascati rather than Castel Gandolfo, for us to draw any tentative conclusions. We do not even know if Voynich was told where exactly the manuscripts had been stored. Or even if he knew, he may have decided to at least keep his promise in that respect. The above-mentioned scenario where Voynich received the volumes from Strickland was also considered by Potenza. In addition, it is also possible that ELV misremembered some of the details (60).

I am grateful to the Historical Archives of the Pontifical Gregorian University (Archivio storico della Pontificia Università Gregoriana) in Rome, in particular Lorenzo Mancini, for the valuable information about their history; to Maria Macchi of AEMSI for the opportunity to research inthe archive, and her help during this search; to Christine Grafinger of the Vatican library for many helpful suggestions, and to William Voelkle of the Morgan Library for additional helpful information. Several newspaper clips were found by Ellie Velinska. The location of Villa Torlonia in Castel Gandolfo was found with significant help from Michelle Smith.

|

|

|

|