|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

While studying the history of the MS, from time to time I run into remarkable, funny, coincidental or otherwise interesting points related to the manuscript or its owner Wilfrid Voynich, which, by themselves, are not too important. They are collected on this page. Newer stories are added at the top. (This also explains the rather unusual numbering of footnotes).

Perhaps the earliest known record informing us about the history of the Voynich MS is the letter from Johannes Marcus Marci to Athanasius Kircher, which Voynich found inside the MS. This letter describes how it was sent from Prague to Rome, as a gift between friends. The letter is discusssed in some detail here. A footnote to this description already hints at the confusion that has existed about the date of the letter, and here we will unravel this issue in more detail.

In Voynich's first presentation about the MS (39) he refers to the letter as follows:

[...] the document bearing the date 1665 (or 1666) that was attached to the front cover.

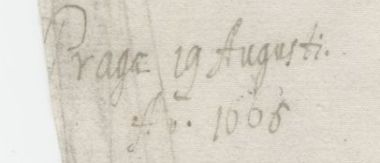

In correspondence related to the letter, still preserved at the Beinecke Library, the date is variously given as 1666, or a typewritten 1666 where the final 6 is overwritten by hand into a 5. In literature, also no consistent date is presented. Barbara Shailor's curatorial description of the Voynich MS (40) states: "1666 (or 1665)" and D'Imperio (41) writes: "in [the year] 1665 or 1666". In the most recent 'official' publication of the MS, the Yale photo facsimile edited by Ray Clemens, the year is given as 1665 (42).

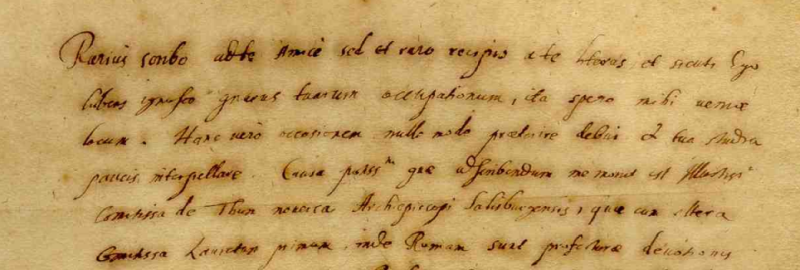

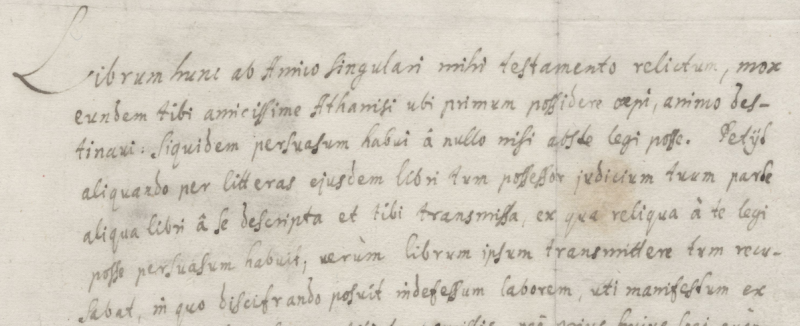

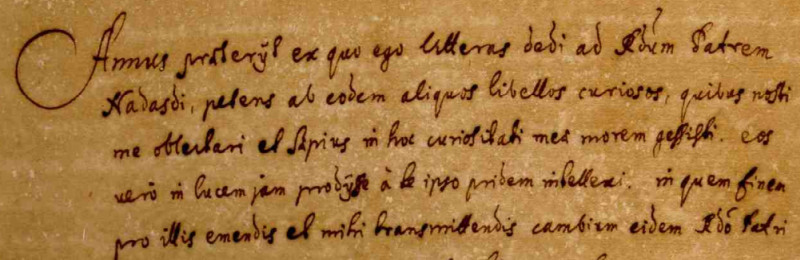

Before looking at the letter in detail, it is important to point out that well over 30 letters from Marci to Kircher have survived. All other letters (that we know about) are preserved in the historical archives of the Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome (APUG). They have all been digitised. They span the time frame 1639 - 1665, and the letter now preserved in the Beinecke Library is the penultimate one. They are described on >>this web page by Philip Neal. Almost all letters are in Marci's own hand, but the final two, including the one in the Beinecke Library, were written by a scribe (43). This is shown in the following figures showing excerpts of three letters: (1) a Marci autograph dated 23 February 1659, (2) the letter now in the Beinecke, dated 16 August 1665 and written by a scribe and (3) the final surviving letter dated 10 September 1665, written by (presumably) the same scribe. Both these letters were signed by Marci in his own hand. The reason for this procedure is undoubtedly Marci's deteriorating eyesight (see also his bibliography).

1 (below) Autograph letter, preserved in APUG

2 (below) Letter by a scribe, preserved in the Beinecke

3 (below) Letter by a scribe, preserved in APUG

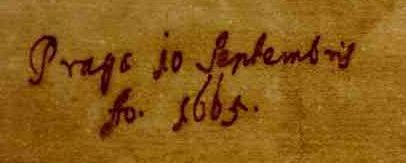

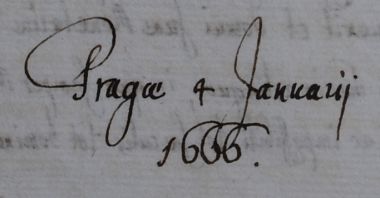

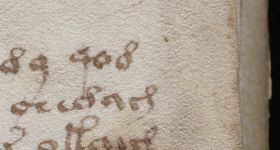

The dates of the last two letters were equally written by the scribe and are shown below:

In the second image the year is undoubtedly 1665, and this example may also help to propery read the year in the first image. The two sixes in the middle are very similar, but the final digit has a clear break in the middle where the bottom of the half circle of the five starts. Even more clearly, it has a right-angle hook at the top bar.

There is, however, further evidence that proves beyond all doubt that this letter was sent in 1665, and this evidence was already presented in the Yale photo facsimile (see note 42). This evidence is contained in a letter from Marci's friend Godefrid Aloysius Kinner, also to Athanasius Kircher, and preserved in the same collection as Marci's letters. This letter is dated 4 January 1666 (see below).

In this letter, Kinner writes (translation by Philip Neal):

Not long ago our mutual friend D Marcus passed on to me what you had recently written to him. Oh how you thrilled the old boy because you said his Philosophia had actually been read by you. It seems to suit the taste of few others. You will be the occasion of even greater joy if your craft and skill can uncover the interpretation of that arcane book which he gave up to you, and I would dearly like to know myself.

This shows that the book that Marci sent to Kircher for interpretation was already sent before 4 January 1666, and 1665 has to be the correct year.

People who have become more than superficially interested in the Voynich MS ("Voynich fans" in the following) will be aware of names of people and places that most other people will not know. There is Wilfrid Voynich himself, the Beinecke library where it is preserved, Villa Mondragone where it was supposedly discovered, and Athanasius Kircher, Johannes Marcus Marci and Jacobus de Tepenec who all owned it at some point.

But what do we know about these people and places. Are they just famous because of the Voynich MS. Or are they famous in their own right? Let's look at each of them.

The Beinecke Library is not just known to Voynich fans, but across the globe, because it holds the Voynich MS. At the same time, it is also one of the most important libraries in the US when it comes to owning medieval manuscripts. It may well have the largest collection of any US library, where competition is coming from the Huntington Library in California, the Morgan Library in New York and just a few more (37).

Verdict: definitely famous in its own right.

Wilfrid Voynich, even more than the Beinecke library, owes his global fame to the manuscript that deservedly carries his name. But what about the rest of his career? Should Voynich be considered one of the most famous old book dealers of all time?

Librarians and people interested in the history of the book will be very familiar with his name. He sold a great number of old books to private collectors and to libraries, and many of these private collections are now equally hosted in libraries. At the same time, he should not be ranked at the top, and he mostly dealt with items of moderate quality or interest.

Verdict: well known mainly to specialists.

Until recently (38) Villa Mondragone was known as the place where Wilfrid Voynich discovered the Voynich MS, and many people know its name because of this. It is one of many villas surrounding the city of Frascati, and the largest, but not the most famous, nor the most beautiful. This is partly due to the fact that it is only partly visible from the city, and not generally open to the public. It has its place in history as the location where the Gregorian calender reform was put into effect, and nowadays it hosts numerous events.

Verdict: somewhat known, but primarily because of the Voynich MS.

Athanasius Kircher is the exception in this short list. Voynich fans will know that he was a famous Jesuit scientist. Possibly, he is the best known of all historical Jesuit scientists, and that has nothing to do with the fact that he once owned the Voynich MS. His fame derives entirely from his character and his works. The list of books and articles that have been written about him is endless and the Voynich MS plays no role of any significance in any of them. What Voynich fans are not necessarily too much aware of is that he was a very unusual Jesuit, primarily interested in science (and, admittedly, pseudo-science) and much less in religion.

Verdict: definitely famous in his own right.

Johannes Marcus Marci was a scientist like Kircher and both are usually mentioned in the same breath by Voynich MS fans. However, he is far less famous internationally. On the other hand, in the history of Bohemia and the Czech Republic, he is well known as the main exponent of the scientific revolution, at the times of Galileo, with whom he even exchanged a letter. Beside a scientist he was a successful physician, and the private physician of several Habsburg emperors. In publications about him, his ownership of the Voynich MS tends to be noted, but also plays no major role.

Verdict: well known mainly to specialists.

Voynich fans know Jacobus de Tepenec as someone at the court of Rudolf II, who owned the MS because he wrote his name in it. But that is about it. Only specialists in the history of Bohemia are likely to have come across his name for any other reason. Several interesting aspects of his life have been recorded by historiographers, in publications only known to experts.

Verdict: essentially only known because of the Voynich MS.

So here is my completely subjective ranking from most to least famous "if it weren't for the Voynich MS".

The cover of one of the many self-published books about the Voynich MS made me realise that there is something very, very funny going on.

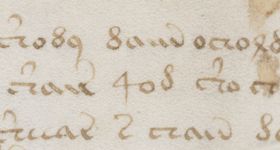

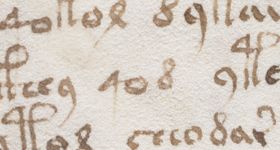

In 1969 the Voynich MS was donated to the Beinecke library by Hans P. Kraus. The library assigned it the next free number in the ranks of early manuscripts: MS 408. This number only became associated with the MS in 1969.

So how can it be that this number occurs frequently in the text of the Voynich MS, which was written in the 15th century?

|

|

|

Surely, this cannot be a coincidence. I can think of only one explanation: the Voynich MS was made by time travelers.

Now just in case anyone thinks that I have finally lost it, there is actually a point to be made here. This is that it is possible to find evidence for any hypothesis in the MS, if one looks hard and long enough.

One of the earliest known owners of the Voynich MS: Jakub Horčický, was ennobled by Rudolf II of Bohemia in 1608. A biography of Jakub is given here. Jakub had actually requested this nobilitation in a letter to the emperor, written probably in October 1608, in which he chose the predicate de Tepenec. The agreement from the emperor came within a few days. In scholarly circles it is not known why he chose this predicate, but it is also clarified that it was not unususal for people to select a predicate that bore no known relationship to them (35). There is no doubt, however, that his predicate refers to a historical castle in Moravia.

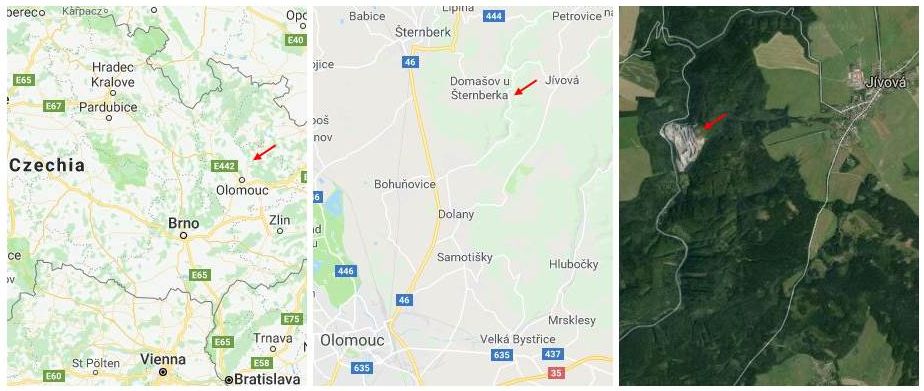

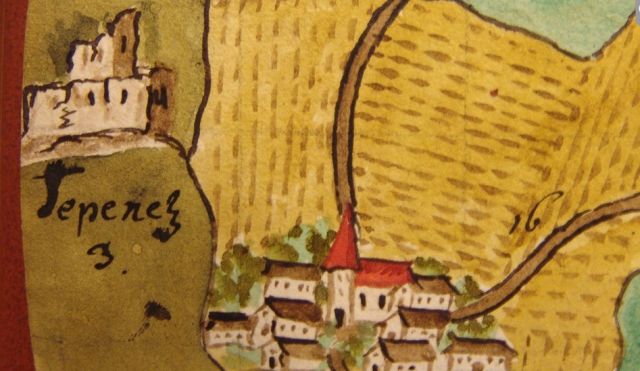

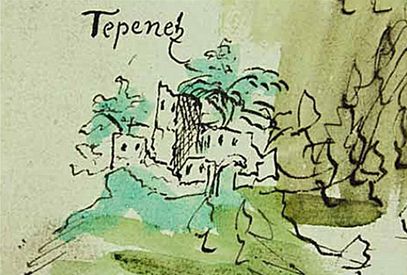

Tepenec castle no longer exists, but it was located near Jívová in Moravia, Czech republic. The castle was built by Emperor Charles IV between 1340 and 1346, and was originally called Twingenberg. It was known more popularly as the Karlsburg. The hill on which it stood was also named Tepenec, but it was later renamed the Rottberg (36). The following series of maps zoom into the location of the castle.

Already in 1405 the castle is reported to have been razed to the ground. Still, it appeared in a map of 1724, and considerable remains of the castle were still visible in the early 19th Century. In those days, the hill was already used as a quarry, among others for the stones of the sidewalk in Olomouc. This quarry has expanded, and is clearly visible in the satellite picture that is part of the maps above. Minor remains of walls were still visible until recently, but it is believed that these are now also lost.

It remains unclear why Jakub chose Tepenec as his noble predicate. During his lifetime the castle was already a ruin. His mentor, Martin Schaffner was from the nearby Olomouc, and perhaps also Jakub came from that province, as explained in his biography.

Here, I used to have a piece of fiction, providing a possible scenario how ELV learned from Wilfrid Voynich where he acquired the Voynich MS. These details were later reflected in her letter to be opened after her death.

However, in July 2019 I decided to remove this piece of fiction for two reasons. First of all, it could be misunderstood to represent my true understanding of events, which was never the intention. Secondly, additional research is bringing up new information, and some of this has already made the story incorrect in several points.

We are used to the statement that the Voynich MS is the most mysterious MS in the world. Its status as the most mysterious, and in fact the most famous MS in the MS collections of the Beinecke Rare Book and MS Library of Yale University eventually led to the publication by Yale University Press of a photo facsimile of it (33).

Part of the history of the MS is documented by Jesuit sources, and in the essay related to this history (34) I used letters preserved in the historical archives of the Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome. I also visited the archives in June 2015, where I learned more than I could have anticipated. In recompensation for the valuable support from the historical archives, I sent them a copy of the photo facsimile, which was gratefully received, and prompted the following text on the >>blog of the historical archives:

In this volume we can find several contributions and full reproduction of the most enigmatic and mysterious book preserved in the Library of the Roman College.

So there we have it. The Voynich MS was also the most mysterious book included in the historical Jesuit Collegium Romanum library.

Updated: 1 May 2018

In 1999 I was able to confirm that the earlier owner of the Voynich MS, who was mentioned but not named in the Marci letter, was called Georgius Barschius. This was well before all of the present active bloggers about the Voyich MS became involved in it, and the story is probably interesting enough to recount.

At the time, the main source for information about the Voynich MS was the well-known book by Mary D'Imperio (The Voynich MS - An Elegant Enigma) (24) and as she clearly writes, the identity of the previous owner was still unknown. D'Imperio only mentions John Manly's suspicion that this may have been Dionysius Misseroni. Interestingly, this was actually based on a misunderstanding. Manly writes that in Marci's book 'Idearum Operatricium Idea' the author refers to his mother in law 'Laura', who is the daughter of Dionysius Misseroni. In fact, Laura, wife of Octavio Misseroni, was indeed his mother in law, but she was the mother of Dionysius, not the daughter (25).

A better hint was found in Brumbaugh (1978) (26), who includes the following passage on pp. 135-136:

1) In looking through cartons of material in the Beinecke Library files, I came across what seems an unaddressed and undated carbon of a translation of a note from Prague to Voynich. [...] This was apparently in response to an inquiry about the identity of the owner who had the manuscript between the death of de Tepenecz and its acquisition by Marci. This was the owner about whom Marci wrote, that he was determined to solve it. The note says that Marci probably inherited the manuscript from George Barschius, an alchemist, since "Marci inherited Barschius' alchemical library." Since the Bohemian Archives proved right in every other piece of information supplied - for example, the identity of "Dr. Raphael" - this is worth following up.

On p.137 he writes that during a visit to Prague he discussed the Voynich MS with the historian Zdenek Horský, but the latter could find no record of Barschius and this is where this episode in 1978 ends, and the name of Barschius was largely forgotten.

Interestingly, again there is a minsunderstanding here, but this was only realised much later: the reference to Barschius was not coming from the Bohemian State Archives to Voynich, but was a question from Voynich to the archives, as we shall see below (27). Still, the point highlighted by Brumbaugh is of great interest, since Marci writes in his letter that he inherited the Voynich MS from a close friend, and this could be the inheritance in question.

In the late 1990's I was reading up on the lives of Kircher and Marci, and found a paper written by John Fletcher with the title "Johannes Marcus Marci writes to Athanasius Kircher" (28). Gabriel Landini managed to find a copy of it and sent it to me. In this paper, Fletcher describes (almost) all letters sent by Marci to Kircher that are contained in the Kircher correspondence ("Carteggio Kircheriano"), which is still preserved in the Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome. He also mentions a friend of Marci called "Georg Barsch", most probably the Georgius Barschius referred to by Brumbaugh.

Another paper of Fletcher (29) included a complete list of all authors of letters contained in this Carteggio, and indeed, there was one letter from "Baresch, Georg" to Kircher. On 24 March 1998 I wrote to the Voynich mailing list that I had added the likely identity of the manuscript's unknown owner prior to Marci to my website (a pre-cursor of the present www.voynich.nu, which was then on Geocities). Following are excerpts of the relevant page, courtesy of the wayback machine:

From the letter of Johannes Marcus Marci to Athanasius Kircher, attached to the manuscript, we know that Marci sent the manuscript to Kircher in 1666 (or 1665) [sic], as soon as it came into his possession as the result of an inheritance from an intimate friend. This friend, who is not named, is further reported to have sent some transcribed portions of the manuscript to Kircher at an earlier date. The question what Kircher has done with the manuscript and why it is not mentioned anywhere in his vast literary output has been asked before.

[...]

Can the person who bequeathed the Voynich manuscript to Marci be identified from the carteggio? It contains more than 2000 letters from over 750 different correspondents, so this task seems almost impossible. Furthermore, access to the carteggio has only been granted to a few specialists. Fortunately, we are helped by the industry of W. Voynich, the helpfulness of the Bohemian state archives and the good eye of R. Brumbaugh. The latter reports (Brumbaugh, 1978) that a letter sent from Prague to Voynich, also contained in the Beinecke holdings, indicates that Marci at one time inherited the alchemical library of one George Barschius. Who was he? Czech experts in Prague could not identify him(3). Alchemical experts have not heard of him before (McLean, 1998). But there is one letter from him in the carteggio kircheriano (PUG 557, fol.353) and he is also mentioned in one letter from Marci to Kircher (who Calls him Georg Barsch; PUG 557, fol.127). (Fletcher (1972)). From this, we learn that Barsch visited Kircher some time prior to 1639 and sent him a letter in 1639. Additionally, Marci writes in his first letter from Prague after his own visit to Kircher in 1640 that he is forwarding Kircher some notes drawn up by Barsch, this man so erudite in the science of chemistry.

The evidence is compelling, but it will be necessary to verify the contents of the letters by Barsch and Marci, and to search for the notes once attached to Marci's letter.

[...]

The history is far from complete and much needs to be verified and possibly corrected:

Access to Kircher's correspondence will be possible from 1999, when it will be made available for study(4). At this time the details of Barsch' letter, his handwriting and the presence of transcriptions of the Voynich manuscript can be investigated.

[...]

The origin of the manuscripts sold in 1912 at the Villa Mondragone is likely to have been documented. Some information is probably contained in the archives of the Pontificia Università Gregoriana, in the Archivum Romanum Societatis Iesu (ARSI), in the Beinecke library holdings or in the Vatican library (notes of E. Carusi, see note 1).

When I wrote this, I had already started with the task of getting a copy of the letter from Barschius, but this was of course a much more difficult one. I had no hope of getting access to the archives in the Gregorian University, but a number of microfilms of the carteggio had been made. One was preserved in the "Knights of Columbus" microfilm archive in St.Louis, but a request for information remained unanswered. A second one was in the hands of Commendatore Olaf Hein, president of the "Internationale Athanasius Kircher Forschungsgesellschaft e.V., Wiesbaden/Rom" (International Athanasius Kircher Study Society). Wiesbaden is only a stone's throw away from where I live, so this seemed an excellent possibility.

Finding out more about this society and its president turned out to be far more difficult than anticipated. There was no address, and the only internet references available at the time indicated that Olaf Hein and his collaborator had secured exclusive access to the Kircher carteggio, and were in the process of publishing it. John Fletcher had been the last person to be granted access, in the 1970's. Since Hein had published one or two papers through the publishing house Harrasowitz in Wiesbaden, I asked them for an address of the society, which they were indeed able to give me. I wrote a letter to the society on 1 March 1998, and only one week later I received a friendly response from Dr. Olaf Hein.

He wrote that the edition of the correspondence, his life's work, was destroyed during printing as a result of several events. He did own a complete microfilm, but was not allowed to show it to anyone. I could certainlly write to the Gregorian University with a request for reproduction, but he advised me that such requests were only granted in very rare circumstances. This left me less than hopeful.

In the course of these events I also came in contact with the Dutch author Anton Haakman, who had written a book (which has appeared in Dutch and Italian only) titled: "the undergound world of Athanasius Kircher" (30). This is a romanticised account of Kircher's attempts to translate Egyptian hieroglyphs, and the story of the publication of his correspondence by O.Hein and his associate mentioned above, though he changed the names of the latter two. A fascinating book, opening a surprising world of intrigue. I was struck by the fact that Haakman also had to contact Harrassowitz in order to get into contact with O.Hein. He had interviewed them, and also made a TV documentary which, unfortunately, I have never had the opportunity to see.

When all hope seemed lost, I found out that a new project had been started by the Institute and Museum of History of Science in Florence with the collaboration of the European University Institute, to digitise the entire Carteggio Kircheriano, and make it publicly available. On 7 March 1999 I mentioned this on the Voynich mailing list. The project was led by Michael John Gorman and Nick Wilding. When I wrote to them about the potential interest of a letter from a relatively unknown correspondent 'George Baresch', they promptly and generously sent me a transcription of the letter in question, saying this was 'normal scientific collaboration'. Consequently, I could announce to the mailing list on 20 June 1999 that the ownership of Barschius was confirmed.

The digitised images of the entire correspondence became available some time later, and these allowed all to see the handwriting of Barschius, but also to find additional references to the Voynich MS in two letters from Godefrid Aloys Kinner, all of which are discussed on this page with references to the great efforts in transcribing and translating by Philip Neal.

While the story of the discovery ends here, it only became clear much later how the name of Barschius turned up in the first place. The source for the information that Marci inherited the alchemical library of Barschius was later found by Rafał Prinke in the work of Zdeňek Servít (31): this fact is mentioned in Marci's book "Philosophia Vetus Restituta" and the relevant quote is shown here. Servít was closely collaborating with Josef Smolka, who had also studied the Kircher Correspondence in the archives of the Gregorian University in the late 1960's, and published a paper about it in 1970 (32). Smolka also acquired a microfilm of the correspondence. His paper also mentions the letter from Barschius to Kircher, though without giving any details.

In 2014 I found out from a letter preserved in the Beinecke library how Voynich obtained the name Barschius. Garland refers in a letter to Voynich to the fact that, in March 1921, "Miss Howe", one of the staff in his London book shop has written to Voynich about Marci's book "Philosophia Vetus Restituta". The relevant quote is given here.

It is also of interest to come back to Brumbaugh, who went to Prague and asked Zdeňek Horsky about Barschius. Had he asked Josef Smolka instead, the identity of Barschius as the previous owner of the Voynich MS could have been established there and then.

As a kind of postscriptum, in the last paragraph that I quoted above from my old web site, I referred to documentation of the sale of manuscripts that I was hoping to find. It took me till April 2014 to find a reference to exactly this document, in an online copy of Kristeller's "Iter Italicum".

I assumed that the year 1913 was a typo for 1912. It took me till June 2015 to obtain a copy of it. The original in the Gregorian University has not been found, but a copy of it had indeed been preserved in the Vatican library. It turned out also that 1913 was indeed a typo, not for 1912, but for 1903, surprisingly. But that's another story.

Raphael Mnišowský de Sebuzín et de Horstein (see his biography) is forever linked with the history of the Voynich MS because he is mentioned as a source of information about it in the letter from Marci to Kircher that accompanied the MS to Rome. How much he really knew about the MS, and particularly about its origin, is not known. Raphael was deeply interested in alchemy and in secret writing, so the Voynich MS is very likely to have interested him. He was also a minor poet, who wrote more than 500 epigrams, which are collected in his book Funebria Raphaelis. We will take a brief look at this book here.

The book's longer title explains that he published it in 1644, at the age of 64. The author's name is listed here as Raphael Mnišowský de Sebuzín et in Lochkow. The main topic of the book is his own death, which he assumed, predicted or knew to be in that year. Most entries are short epitaphs for himself. The book has a portrait that is very similar to the IMG: one shown in Pelzel, but it is more lively and has more detail. It was most probably used as the model for the illustration in Pelzel (1773) (23). All epigrams are grouped into sections with titles such as: Peregrinatoria , Linguistica , Patronalia , Uxoria , Alloquialia Exotica, Aenigmatica , and many others. Following are a number of epigrams that I noted down, as they intrigued me for one reason or another.

XXXVIII

Lingua quidem poliglossa mihi, sed fallere Parcam,

Non poteram, ignarus qua loqueretur eram.

(Here he describes himself as a polyglot)

XLVIII

Procurator ubi? In Sepulchro ibi. Ah sit

Sit sententiamitis, inquito, illi.

LVI

Haec Scrobs, haec camera, est mihi sepulchrum,

Sic me Scrobs-Camerarium vocate.

LXVI

Servivi tribus et decem ter annis

Tribus Caesaribusque Regibusque.

Sed mors, sessus es, inquit, i quiesce.

CIX

Rapha Dei Raphael, morborum Archangele Praefes,

Rapha Dei, morbi sis medicinae mei.

CLXXXVI

Hic Raphael jaceo, Raphaelem si quis amasti

Adde precem: florem, rorem, apagges adde precem

CCXXVII

Sexaginta annos, et quattuor, absque Podagra

Vixi, multum auri non fuit ergo mihi.

(next)

Multum auri non unus habet, Podagra, Chiragraque

Attamen ille caret : quare aliunde malum est

(next)

Hicce quidem iaceo, sed ne podagrosus haberer

Suecidit sanos mors mihi falce pedes

CDXXXVIII

O Seneca Seneca, te neca, sic Nero jubet

Intrepidus ergo et glorius moriar senex

CDXL

In Seneca fera nex, medicum Rapha in Raphaelis est.

Hic subit et tolerat, vitat at iste necem

CDXLIV

Quod non sis Nigromanticus Tritemi,

Ipsum ad tactum oculumque comprobandi.

De menastore colloquemur illic.

CDL

Quid super Evestro confingas Helvete Bombast

Non capio. Capio quidpiam inane dari.

CDLIII

Nil Evestrum operatur ante mortem,

Nec post. Namque tuus manet, manebitque

Azoth, cognitus haud mihi, ante, nec post.

CDLV

Ex Inferno Avicenna scripsit ad te,

Dem fidem tibi, tanta mentienti ?

Nulla scriptio venit, hinc, vel illinc.

CDLXVIII

Glorificatur ubi Corpus, cum mente, simulque

Jungitur. Hoc sic sic. Yr Xyr Elixir erit.

CDLXII

Seneca, Boetius, Cebes, Panaetius,

Consent mori esse bonum, et id ego putem, malum?

Bonum quod est, opinion non sit malum?

CDLXIV

H. D. M.

Manhu quid hoc. Manhu quid hoc.

Et hoc, et hoc. Vel hoc, vel hoc.

The phrase Manhu quid hoc appears at least 4-5 times in subsequent verses. One of them has another abbreviation as heading: AM. PP. D.

CDLXXII

Cui non dictus Hylas Maronianus ?

Cui non AElia Sphyngis instar illa ?

Cui non Laelia mira Styrps et illa ?

Desudavit apex Sophorum in illa,

In re tam facili, imo tam pusilla.

Dicam namque Chymera quae si tilla.

CDLXXIII

Non Aqua, non Aer, neque Amor neque mens neque prima

Materies, neque Mercurius, neque Petra Sophalis.

Non Niobe, neque Fama. Sed est Idea Platonis.

Est Icon mea, veltua; qalem (sic) mente reflexa

Abstrahis, et sepelis, et qualem in imagine cernis.

DXII

O Mors Cur Deus Negat Vitam

Super

Be Te Bis Nos Bis Nam

Manhu quid hoc? Mera Babylon.

In a second one, the above two rows of words are written in columns, with super between each pair: "O super Be", "Mors super Te", etc..

DXIX

Papae quid hoc? Merum Nihil.

Annon meum nomen vides?

DXXV

Mors Steganographicas Sermonum exosa latebras,

Simpliciter dixit. Nec tibi parco, veni.

DXXVI

Absenti Parcae Steganographa misi. Ea vero

Praesens praesenti voce locuta mihi.

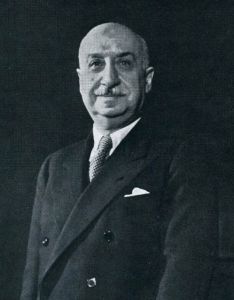

Tammaro de Marinis was a very successful antiquarian book dealer (7). Kraus writes in his autobiography (8) that he never met Voynich, but de Marinis did meet both of them in the course of his life. De Marinis may or may not have seen the Voynich MS, but he has a role to play in the history of the MS. He was born in Naples in 1878, and according to his later associate Forti (9) he 'did speak only a bad...Neapolitan dialect' (10). He worked for Olschki in Florence until 1904, when he started his own antiquarian book business, possibly already in association with Forti. His shop ('Librairie Ancienne T. De Marinis & C.') was located in Via Vecchietti nr. 5 in Florence.

| Portrait | His shop (original photo) | Modern photo of the location |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Wilfrid Voynich became his competitor in 1908 through the acquisition of the Libreria Franceschini also in Florence. However, when Voynich acquired his famous collection of approximately 30 manuscripts from the Jesuits, he seems to have struck a deal with De Marinis, and we know from several sources that De Marinis obtained a number of these manusripts. In a letter written by Voynich to Belle Da Costa Greene (11) he writes that the best of these manuscripts were already sold to booksellers in Florence, but gives no name. From Ruysschaert (1959) (12) we know that several of these manuscripts are mentioned in a catalogue of De Marinis issued in 1913 (13) and in a book he published in 1947 (14). Comparing Ruysschaert (1959), his source (15) and De Marinis (1913) we find that this set comprised seven manuscripts. They are indicated in a table on the page describing the MSs Voynich acquired from the Jesuits.

This deal was not only very lucrative for Voynich, but also for De Marinis. In his 1913 catalogue, two of the seven manuscipts were already listed as 'sold', namely manuscripts of Cicero and of Didymus, both originating from the library of Matthias Corvinus (i.e. before they entered the Collegium Romanum library). These rare and highly valuable manuscripts were sold to John Pierpont Morgan sr., and we learn a number of interesting details from the Forti letter (see note 9). Forti had been to Budapest in order to sell the manuscripts back to Hungary, but they were not able to raise the desired price. Instead, they were sold to Morgan's preferred supplier in Italy: Alexandre Imbert. The invoice from Imbert to Morgan is also still preserved. From annotations on the Forti letter we learn that Voynich got 300,000 Lira for the pair of MSs, i.e. approx. 60,000 US Dollars in 1912. Furthermore, we learn that this deal allowed De Marinis to acquire his 'Villa di Montalto' just outside Florence.

What is perhaps even more interesting is that these two manuscripts were well known to Hungarian historians. They had been photographed by Flóris Rómer in 1871, while they were still in the Collegium Romanum (16), and later historians were looking for them in vain in Rome after the confiscation of the Jesuit libraries (17). When they were presented in Budapest, they were immediately recognised as the two manuscripts that used to be in the Jesuit Collegium Romanum (18). It is therefore also clear that De Marinis knew the provenance of these manuscripts but, like Voynich, he remained silent about this (19).

Three of the other manuscripts that De Marinis obtained from Voynich trace back to the Naples library of the kings of Aragon, on which he was later to publish an enormous 5-volume book (see note 14). While in his 1913 catalogue he does not mention anything related to the provenance of the 7 items we know he got from Voynich, in this book he writes for two of the items that he obtained them in Rome, from the London dealer Wilfrid Voynich. Additionally, this work includes an Annex written by Mgr. Jos Ruysschaert, so we also see that De Marinis and Ruysschaert knew each other, and it is no surprise that Ruysschaert refers to De Marinis' books in the footnote in his catalogue, when speaking about Voynich.

After his sale (through Imbert) of the two manuscripts to Pierpont Morgan, De Marinis went on a commission to acquire part of the MS collection of Abdul Hamid II for him. He succeeded, but when he returned to Italy, Pierpoint Morgan died (March 31, 1913). The transaction did not come about, and he only managed to find a buyer after the First World War (20).

During the first World War, De Marinis and Forti split their business under some controversy, and De Marinis continued until 1924, when he sold his business to Hoepli in Milan. In the course of time, he obtained the title of Commendatore, and became associated with the Grolier Club in New York, where he is listed as one of the few honorary members. When, in 1962, the Grolier Club decided to organise a study tour to some of the most important libraries of Italy, De Marinis was one of the main facilitators of the trip, using his reputation and contacts with the many libraries (21). One participant of this trip was Hans P. Kraus, so on this occasion De Marinis and Kraus met. One of the places visited in the course of the tour was De Marinis' Villa di Montalto, already mentioned above. We may wonder to what extent De Marinis and Kraus talked about Voynich. It was also on this trip that Kraus met Mgr. Ruysschaert in the Vatican, and asked him about the Voynich MS (22).

Forti survived De Marinis and reached the age of 99. It is not clear what happened with De Marinis' papers, but we probably would not learn much from them about the Voynich MS and the other manuscripts, given the strict secrecy that both Voynich and De Marinis maintained on this topic. However, it may well be worth the effort to search for them.

Following is a transcription of a letter Anne Nill wrote to ELV on 14 March 1936. Nill is working on the index to the first edition of De Ricci (1937) (5), in the Washington Library of Congress.

Dear E.L.V.

I must get today s rather dramatic little episode (which was in the true Voynich style) off my chest at once, or I shall make no headway with the mountain of weekend work waiting to be done though the weather is fine and I should be out to take advantage of it.

This morning I vaguely noticed that Dr. Jameson was taking a visitor, who looked obviously Jewish and obviously a scholar, through the manuscript division, and was introducing him to more important members thereof. I paid little attention to them since I, of course, was not introduced. Later I went to Dr. Wilson s alcove to give him a letter I had just written, which I stopped to discuss with him. Just then Mr. Wilson came in with the visitor and I realized that he wanted to introduce him to Wilson, so I withdrew tactfully, and with dignity! I soon became absorbed in my Index and forgot about them all. Suddenly I realised that the visitor was being brought by Wilson into my alcove. The latter looked at me with a twinkle in his eye, and said: Miss Nill, I d like to have you meet Dr. Salomon (pause....), of the Warburg Institute! It seems (though I was blissfully unaware of it) that as soon as Wilson learned that Dr. Salomon was connected with the Warburg Institute he asked him if he knew about the Voynich Cipher Ms.; and, as Wilson afterwards put it to me, as soon as Dr. Salomon learned of my presence in the library he became more interested in meeting me than in doing anything else there. Well, to make a long story short, Wilson left us alone together, and we talked and talked, and the entire Manuscript Division was mystified as to why a distinguished visitor who had been taken about and introduced to all the high and mighty ones should wind up in my alcove and remain there in earnest conversation with me. It was all very funny. To get back to more important matters. Dr. Salomon is none other than the very person for whom Dr. Panofsky took back our set of Photostats. When he returned to Hamburg he laid them on Dr. Salomon s desk (as I heard today) , and said: Here is something for you. Do you remember Panofsky telling us that he wanted them for his colleague who was then working on a mysterious Vatican MS. (I wrongly got the impression that he meant Prof. Liebesch tz, the author of the book on Hildegard of Bingen). Well, Dr. Salomon is the one who has been working on the said Vatican Ms. (6), and his book on it, by the way, is just about to be issued. He is coming back to the Library of Congress on Monday to show me the page proof (there will be more excitement in the Division when that happens).

We talked about the Cipher Ms., Germany, the position of the Jews there, etc. etc. It appears that he has done considerable work on the Ms. (he says he takes it up every few months). He thinks it may be German ( you will recall that Dr. Panofsky told me something of that when I ran across him in the Morgan Library in 1934), but that he is not yet absolutely certain of this. He is convinced that it was written in the 15th century, possibly as late as 1450, possibly earlier in the century. He told me some interesting things about it, but I have not had time to think about his remarks sufficiently to put them down clearly. I hope to be in a better position to do so on Monday, after I have compared my notes with Wilson s (he also discussed the Ms. with him). Dr. Salomon thinks possibly the text may be of no great significance, but cautiously adds that until it is deciphered one cannot tell. Scholars, he continued, are attracted by a mystery.

Wilson was most interested in this interruption of our work. When I told him that Dr. Salomon plans to come back on Friday to show us the page proof of his book on the Vatican Ms. he said: Miss Nill, bring your Photostats of the Cipher Ms. I warned him that if I do that we shall get very little work done on Monday, whereupon he said: Oh that s all right; the Ms. is very interesting, and besides aren t we supposed to be working on Mss. that are to be included in the Census! He never can resist a discussion about the Cipher Ms., and is, apparently, looking forward to Monday as eagerly as I am. I asked Dr. Salomon whether he expects to be in New York, and, if so, whether he would like to see the Ms. He said he plans to be there during the latter part of April, and that he would like very much to see it. I explained to him that you would be very glad to show it to him. He has your address and will get in touch with you. When I see him on Monday I think I shall also sound him out about Dr. Petersen. If he shows a desire to meet him I shall write to Dr. Petersen who could, undoubtedly, go to New York for that purpose if he, on his part, wishes to meet Dr. Salomon. It would be a good thing if I could get these two together.

Isn t all this amazing? To think of meeting unexpectedly here at the Library of Congress the unknown Hamburg scholar who has had our Photostats since 1933, and just as I was thinking for the umpteenth time what a dull and unscholarly (for the most part) place the Library of Congress is. But it seems to be true that sooner or later everybody that is anybody turns up here. And, so far as the Cipher Ms. is concerned I don t suppose I could be more advantageously located, since Wilson is so greatly interested in it and tells everyone about it. Maybe I had better make up my mind for once and for all to dedicate my life to that exasperating manuscript? You see this is all rather a joke on me. For the past week or two I have tried desperately hard to neglect my work on the Ms. I have been buried in the Index, in the Greek and in another Ms. Book of hours which Wilson has asked me to examine from cover to cover, analysing it in accordance with his outline for this work. So I have been busy. But now I shall have to spend my precious Sunday going over all my notes about the Cipher Ms., and pouring over the photostats, so as to be ready for Dr. Salomon on Monday. I can t tell you how much it has helped me, the work I have done on the Ms., in conversations with such men as Dr. Petersen and Dr. Salomon. They really seem to think I know something about it, and that is a useful impression to give if we want to keep up with the work that is being done on it. It looks to me as if it were not intended that I should rest where that Ms. is concerned, me I have about decided to bow to the inevitable and resume my work on it (an hour or more every evening) whether I have the time or not!

The Wilson mentioned frequently, for whom Anne Nill was working, is no-one else than William Jerome Wilson (b.1884), co-author of De Ricci's Census (see note 5). It is clear that the Voynich MS was of great interest to Wilson, and that he will have gotten the info on the estate of Voynich directly from Nill (and ELV) who are the Administrators of the estate.

The foreword of the well-known book by Mary D'Imperio (The Voynich MS - An Elegant Enigma) (see note 24) was written by Brig. John Tiltman. He writes:

From the time when Mr.Friedman's health began to fail, I have acted as a sort of unofficial coordinator of the work of some of the people who have been working on the problem, and when Miss Mary D'Imperio told me of her interest, I suggested that she should assume this responsibility.

In November 2014 I had opportunity to meet Jim Reeds again, after many years. He was attending the opening of the Folger Shakespeare Library Exhibition: "Decoding the Renaissance" (4). Over lunch, with Jim, his wife Karen and Bill Sherman, the organiser of the exhibition, at a diner two blocks away from Friedman's house on Capitol Hill, Jim told me the following. Some years ago he had spoken with Mary D'Imperio. She reminded him of the introduction to her book by Tiltman, and said that she wanted to pass this role on to Jim. Jim then told her that he preferred that it was passed on to me instead, to which she agreed.

I add this to my 'trivia' page, just to have it recorded somewhere. The only kind of coordination I feel can be done is the collection of information, which is the very purpose of this web site.

In 1903 the Society of Jesus decided to sell a valuable collection of medieval MSs to the Vatican. Before the sale was completed, Voynich managed to acquire a number of them instead. A handwritten summary catalogue of the entire collection was prepared in 1903, and it includes almost all of the MSs that Voynich acquired. This document is preserved in the archives of the Vatican library, and it plays a central role on the page I prepared to describe the collection of MSs that Voynich obtained from the Jesuits, including the Voynich MS. For a small number of MSs included in this catalogue we still don't know what happened with them. Voynich was very secretive about the whole event. Did he also obtain them?

One entry in the 1903 catalogue, which I labelled "J19" on the above-mentioned page, is described as follows. In the left column it says: "Cicero M.T". The central column has the main description:

Officiarum _ Cato Maior. Laelius, Paradoxa - cod.ch. s. inc. (forte recentiss. cum notis P. Meretturii

The reading of the name at the end is not fully certain. The abbreviations mean: codex chartaceus saeculae incertae ( = paper MS of uncertain century). In the right-hand margin, an X is written, indicating that this MS did not enter the Vatican library. However, it is also not known to have been acquired by Voynich. Ruysschaert did not include this MS in his tentative list of MSs acquired by Voynich (3). Then again, this list is known not to be fully correct. Sufficient reason to try and find out what happened with this MS. If it was acquired by Voynich, there is a fair chance that it was sold to some American library or private collector.

There is a very large number of MS copies of various combinations of books by Cicero in American libraries, but this on-line >>Checklist of Western Medieval, Byzantine, and Renaissance Manuscripts in the Princeton University Library and the Scheide Library returned one MS with exactly the same combination of titles, namely:

Kane MS. 28: Cicero, Cato Maior de senectute, Laelius de amicitia, and Paradoxa stoicorum, s. XVmed, Italy (Milan?)

CATALOGUE: Skemer, Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts, vol. II, pp. 64 66.

This is of great interest, because this is the library of Grenville Kane, who acquired several of the MSs that Voynich had obtained from the Jesuits. My query to Princeton was responded very promptly as follows:

The Princeton University Library's Kane MS. 28 is an Italian manuscript of the mid-15th century, which was in England at least from the early 19th century, and possibly several centuries earlier, before being purchased by Wilfrid Voynich. He may have acquired it from Maggs Bros., London, which offered it in several printed catalogues. Grenville Kane's acquisitions note indicates that he acquired the manuscript in 1931, which would be after Voynich's death. For a full description of Kane MS. 28, with a long and detailed provenance note, see Don C. Skemer, Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts in the Princeton University Library (Princeton University Press, 2013), vol. 2, pp. 64-66.

So, this MS was indeed sold to Grenville Kane by Wilfrid Voynich! This felt like too much of a coincidence, and my first (mental) reaction was that this was it, and the acquisition from an English seller should be part of a cover story. Of course, the next step was to check the recommended MS catalogue written by Don Skemer. A very impressive work it is, and it immediately made clear that this was indeed another MS, and did not come from the Collegium Romanum. The fact that it is a parchment MS, and not on paper, is just one of many aspects.

Just a big coincidence indeed.

On 2 November 1915, Wilfrid Voynich received a letter from Dr. F.H. Garrison. It is addressed to Wilfred M. De Voynich. His address is given at the Art Institute of Chicago, where he was just completing his exhibition of rare books and manuscripts, which included among others his Roger Bacon cipher MS. Garrison is interested in using this MS in his book on medical history, in connection with Rudolf II. The answer from Voynich is of interest, as he writes on 18 November:

You can use as much as you like the details of the book for your medical history; but it belonged to Emperor Rudolph I., not II.

This misunderstanding by Voynich is reiterated in a letter two years later, to Edith Rickert of the University of Chicago, when he writes on 18 September 1917:

It was purchased by Emperor Rudolph for 600 ducats. He died in 1291 (Bacon died in 1292?). In the early 17th century it apparently passed into the hands of Ferdinand III. It was never outside of royal hands except during two periods when it was given to Athanasius Kircher for transliteration, and when it was acquired by me.

Thus, even 5 years after its discovery, Voynich had not understood many important details of the Marci letter attached to the MS, in particular believing that the Rudolph mentioned in it was Rudolf I of Germany (1218 1291).

The author of the letter is Dr. Fielding Hudson Garrison (1870-1935) and the book referred to is his famous standard work: An introduction to the history of medicine (1913) . In the third issue of 1921, a 943-page volume, we find on page 161, under ancient Irish medicine:

Where footnote 2 says: In the possession of Mr. Wilfred M. de Voynich .

Two years later, in 1917, Voynich and Garrison together published a paper in the Annals of Medical History, Vol.1 on a completely different topic.

One may want to sympathise with Richard Salomon, the German scholar who met Anne Nill in 1936 and maintained a long correspondence with her (1). On 20 May 1953 he wrote to her, having just reviewed the work of Joseph Feely. He was clearly underwhelmed, and wrote:

If Athanasius Kircher's correspondent - the name escapes me (2) - could have foreseen what nonsense his mentioning Roger Bacon's name would produce, he would never have sent the letter.

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|